Last week I made the very opposite of a bold assertion in claiming that the NES classic Super Mario Bros is the gold standard in good platformer mechanics. I also mentioned Tim Rogers and the “sticky friction” that so endeared him to the game; today I’d like to elaborate on that second part.

If Metacritic was around back in 1985 I’m sure you could pull up a whole swathe of reviews describing SMB’s controls as ‘intuitive’, ‘tight’ or ‘pixel perfect’, and these words could lead the uninitiated observer to conclude that Mario is some kind of Olympic athlete when in fact this is (barring certain unfortunate circumstances) patently untrue.

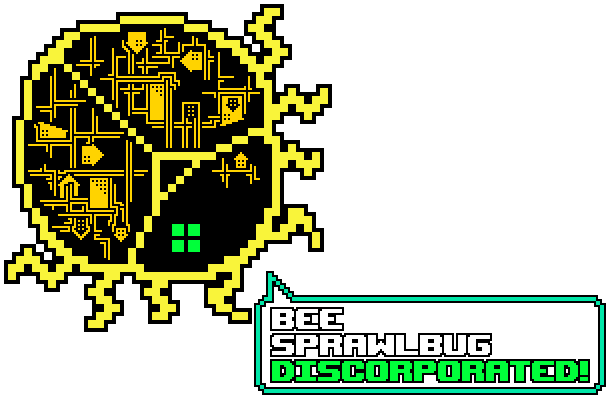

Pictured: Certain unfortunate circumstances

You see, while I was working on my ePortfolio last August I had cause to go back and check, and it turns out that Mario moves not like a gymnast or an action hero, but rather more like a fat guy on ice skates. It takes him a bit of time to really get moving and even longer to stop. Each jump brings not only the possibility of over or under-shooting your target, but also of landing with too much speed and plummeting forward into a Goomba or a fireball or something. Does this sound like ‘tight, intuitive, pixel perfect platforming’ to you? Well, perhaps it should.

As you may expect from a game as highly-acclaimed as SMB, its primary mechanics are all in there for good reasons. Why does Mario move like a fat guy on ice skates? Is the timer on every level there solely to provide an anachronistic, arcade-ish scorekeeping system? Why, on a controller that has two primary buttons, is one of them dedicated mostly to making your dude ‘run’? (And why, exactly, would you ever want to release that button?) The short answer: Going fast is fun. The long answer has to do with difficulty scaling, the design constraints of platform games in the early 1980s, and malevolent cacti.