What is the value of a phantom limb?

In 1964 Marshall McLuhan published a book called Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. It’s sort of like a religious text for media theorists, though it leans more towards apocrypha than canon. McLuhan was a bit of a heretic. He’s most famous for claiming it’s the form of a medium, rather than the messages we send through it, that has the biggest impact on society; not the violence we watch on television, for example, but the structural properties of television itself. Media change the world by changing its users on a fundamental level; by extending our bodies. The printing press is like a bionic mouth that lets us speak to a million people at once even centuries after our death. The internet is like a second face, a new partial self whose disembodied and digital form can both listen and speak to others of its kind. When I adopt a new medium it alters how I experience the world and what I can do to it, as if I had grown a new appendage. Even my Twitter persona, for example, represents a new facet of my body. At the same time, however, Twitter is a web service; a business run by people I can’t trust, yet with whom I nonetheless share ownership of my shiny new-grown limb. If they wanted to they could cut it off and sell it.

I develop videogames for a living, but I spent last year really hating videogames. I questioned how it was I could consume 60 hours of ‘content’ for Assassin’s Creed 3 yet feel utterly unsatisfied by my act of consumption. I questioned what it was I had consumed, other than my own time. I questioned what it was I sought from the game in the first place. I questioned the nature of the ‘content’ it claimed to offer me; privately I began to suspect it might not even exist. The games I was making and playing seemed more and more to me like empty forms: Puzzle boxes within puzzle boxes, each layer promising ‘content’ underneath it yet in the end yielding an empty centre. I became too tired and bored to care about games anymore. I could no longer see the point in it. I felt as if some enormous detritus had gathered upon my career and favourite hobby; that I could no longer reach through this detritus to claim the enjoyment I had once found underneath.

I awoke from my yearlong stupor the night I encountered a game called Problem Attic by a person named Liz Ryerson. It was like nothing I’d seen before. Rather than a puzzle box, it was more of a sculpture. Its ‘content’ was not buried behind teaching, gating or a thousand tiresome transactions; it was simply present, exposed, beautiful anywhere I cared to look. Ryerson had not designed the game to be consumed so much as authored it to contain ideas. We cannot consume an idea. We cannot lock and unlock it; we cannot buy and sell it; we cannot bundle it with an Xbox 360 at GameStop. We cannot possess ideas. But I learned from Attic that ideas can possess us. Attic made kindling of the detritus through which I’d been stumbling, lighting a bright yet tiny fire in the back of my brain. The more I thought about the game the more it changed the way I thought: About videogames, about Marshall McLuhan, about my job, about everything. As I put my thoughts into writing the fire spread, and the detritus began to burn away.

Upon completing Attic I resolved to write a brief close reading, so I sat down one evening hoping to produce 500 words. I stood up the next morning with 4000. Those words became Fashion, Emptiness and Problem Attic. But even as I published that piece I knew I was not finished. I’d learned Attic is a game about prisons of belief and behaviour: It’s not about looking at the path ahead, it’s about looking at the walls. Thus it was not enough to explain what Attic makes present that other videogames leave absent. I needed to understand the forces around me that created this absence in the first place. Another 4000 words later I’d concluded it was the values I internalized as a student of user-centered design (chief among them clarity and craft) that made me champion products I’d now come to hate. These words became The Cult of the Peacock. I liked that piece a lot, but still my work felt incomplete. I had yet to express the entirety of the thinking I’d been doing; columns of flaming detritus still swirled through my head. I’d learned Attic is not just a game about prisons; it’s also a game about jailers. It was not enough to criticize the shape of the prison in which my work was confined. I had to learn who built its walls.

McLuhan, if he were still alive, could tell us all about walls. He would say walls are a medium. By placing them in the world we form a new space that tells us where we can and can’t go, what we can and can’t do. In this particular sense McLuhan might also say that media, all our various technological appendages, function exactly like walls. When using media we tend to focus only on the messages we choose to send and receive through the paths laid out before us. But if we really want to know who has true power in the world we should seek the people designing the path; those who construct, own and operate the media through which we live our lives.

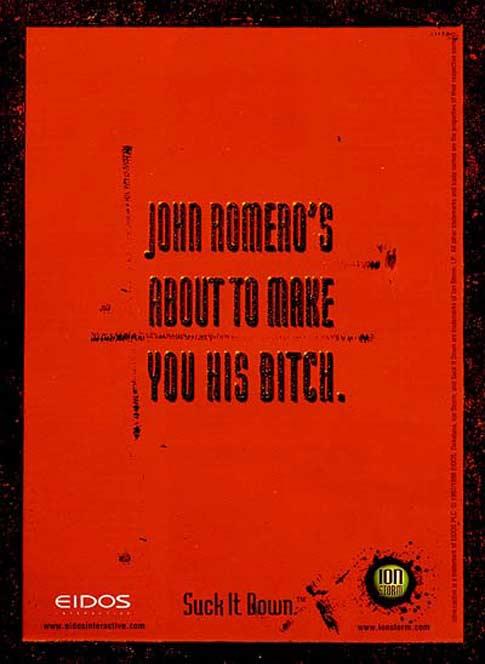

This is a story about how Steam, Twitter and the App Store came to exist. It’s about how these services present themselves as our friends while behaving as our enemies. It’s about how they stole the internet from us, creating a place where everything is ‘free’ but liberty remains unavailable. It’s about how their forebears stole our very language from us, creating a lexicon in which we have no means of even describing that which cannot be possessed and consumed. It’s about how they filled my head with detritus — with garbage — and sold all my new appendages to the highest bidder. Today I come to reclaim them.