In the corporate future nightmare world history has shit upon the notion of ‘fairness’ with such gleeful malice that fairness itself died, and now exists as a ghostly poop joke from some idealized point in the past. That poop joke’s contemporary name is “meritocracy”, for this is the word that captures our longing to establish any causal relationship whatsoever between the work we invest in life and the status we obtain from society.

Meanwhile, in videogameland, it is that special time of year when all our favourite media orgs perform a series of dark rituals to make the ghost of fairness reveal itself (emerging from its toilet bowl to shame humankind). We must commune with it, you see, in our efforts to catalogue ‘the best videogames of 2017’. Why do we do this? I don’t think it’s for posterity, or out of some solemn ethical duty to consumers; in truth I think we do it because we’re desperate to entertain. It’s fun to mark the passage of time by someone’s achievements, instead of by gradual depletion. It’s merciful.

This year I expect Super Mario Odyssey will rank on every major ‘best of’ list in existence: best videogame of course, but also best motor scooter, best shiba inu and maybe even best procedurally-generated porn film. It’s nothing if not a gratifying experience, I guess is what I’m saying.

Because Mario, in his infinite weirdness, has seen fit to appropriate the Homeric epic, this essay shall match its stride by appropriating the early Christian triptych. I offer three worlds for you to conquer: three manifestations of fairness’ shit-soaked ghost. Together they describe what it really meant to be ‘the best’ back in hellish, frightful 2017.

World 1: Actually it’s about ethics in chocolate fudge hills

In a world obsessed by ‘fairness’, our meritocracy’s prime objective is to obfuscate the channels by which participants can buy success. For example (and frankly, there is no better example), consider the culture of AAA videogames. Inform any card-carrying ‘gamer’ that their opponent has just used 99 cents to purchase a modest competitive advantage in Battlegame: Space War, and watch with alarm as they sprout a second row of teeth. Hear them claim it is UNETHICAL to pay money in exchange for victory; hear them speak of the way it encourages gambling, and endangers children, and plays host to corporate greed.

Look around this person’s environment, however, and you might find an expensive computer they use to guarantee the best framerate. You might see their ‘gamer mouse’, or maybe even their ‘gamer chair’, each item arrayed strategically before some fancy digital display that could have cost them four thousand dollars. Have they not ‘paid to win’ in the very manner of which they accuse their opponent? Well, yes and no.

There is a magic circle in place dividing the outer ‘real’ world from the inner, hallowed spaces of our videogame software. We recognize the outer region to be a moribund capitalist nightmarecape in which nothing is fair and few ever get what they deserve. Yet we designate the inside of the circle as our unspoiled meritocratic utopia. We have collectively agreed to ignore the cost of any particular player’s gaming setup. We decline to take issue with the fact that some people can afford more leisure time than others, and might therefore be more practiced; we likewise ignore the fact that getting very good at videogames in the absence of all that leisure time is a recipe for abject poverty. In these ways we hold forth the illusion that within our magic circle we’ve extricated ourselves from wealth, class, infirmity, oppression and all the other problems posed by history. They are of course still present; we simply do our best not to acknowledge them.

While there are many people who suffer from gambling addiction (and companies such as EA remain thrilled to try grifting them) the wider videogame culture has never been known to defend the vulnerable from the wealthy. Why should we accept that ‘actually this is about ethics in videogame monetization’ when no aspect of gamerdom aspires towards ethical conduct? Can its hatred of ‘Pay 2 Win’ mechanics possibly stem from benevolence? I don’t think so. Nor can it be it about fairness, for true ‘fairness’ hasn’t left its toilet bowl in thousands of years.

What motivates them instead is their affection for the magic circle, and their desire to defend it from interlopers. It’s about the illusion of fairness: the careful maintenance of appearances, the way our meritocracy demands. It is a dream we share with each other, perched ever on the verge of wakefulness. To preserve it we have held our eyes shut.

World 2: The performance anxiety sherbet cloud

The next time you’re playing an online competitive game and your teammate loses their shit over some tiny mistake they think you made, consider the specific variety of panic they must be experiencing. How is it that this minor setback, of the sort we humans encounter every day, has driven them to such an alarmingly hateful response?

I think it’s because hatred is what our meritocracy engenders. This person has sought reprieve from the absurdity of the real world within the magic circle of the videogame, trusting a piece of software to transmute their nervous energy into success. They attack their online ranked matches the way bad lovers attack a sexual encounter: hastening wordlessly through the motions, hyper-focusing upon their own performance, and treating their partners more as accessories than as collaborators. They aim to score rather than simply to play, and they’ve hitched their ego to the outcome of the contest.

Because the game’s matchmaking algorithm has dehumanized you in their eyes—selecting fresh teammates each time the same way Amazon selects products that are “Frequently Bought Together”—you exist to them as little more than a fragment of technology. If they suspect you of malfunctioning, they will curse you the way I curse Photoshop every time it hangs for a minute. You are human to them only insofar as blaming you for defeat might help absolve them of failure. In every other respect you are a masturbation tool.

The magic circle leaves no room for bad days at work. It has no tolerance for mental illnesses, or crying babies, or even for having an ‘off night’. It has no interest in accounting for the fact that merely using a feminine-sounding voice invites thousands of years of misogyny to come stampeding through the middle of its algorithms like a horde of angry baboons. By design, it is too ‘fair’ to acknowledge such things. Instead it seeks to maintain the pleasant fiction that the inside remains distinct from the out; yet this distinction is purely illusory, and the illusion is so vanishingly thin that it crackles out of existence every time you make a questionable play. This is why, for the screaming internet person on your competitive team, your irrepressible humanity has become a source of existential horror.

When they howl at you across the internet via their ‘gamer’ branded microphone, it has nothing to do with you specifically; it stems from their exhaustion at having to maintain a meritocratic facade. This machine they purchased to transmute themselves from ‘doomed-ass human’ into ‘competitive athlete’ is, in the end, just another strange distortion of our material history. It alienates us from other people while funnelling time and money through a bureaucratic ranking system; and being bureaucratic rather than authentically ‘magical’, this system is no better a focus for attention than our day jobs, or snack foods, or gambling or anything else. ‘Fairness’, from this perspective, is simply another form of vice to be obfuscated amidst flurries of emotional abuse.

World 3: Nintendo’s castle

On September 1, 2016, Nintendo of America Inc. issued a DMCA takedown notice compelling gamejolt.com to remove 562 of the Mario, Pokemon and Zelda fangames it had been hosting on behalf of its community. It’s unclear how many of these games actually infringed upon Nintendo’s copyrights; fortunately for the big ‘N’, however, clarity is hardly the point. Since the DMCA permits it to employ a ‘shoot first and hold costly legal proceedings later’ approach, the hobbyists working on these games (often twelve year old children) have no hope of mounting any kind of resistance. In the corporate future nightmare world it doesn’t matter whether your work falls into the legal gray area of parody or satire; our governments have sold this gray area to whomever can afford lawyers and lobbyists. They have sold it, in other words, to Mario.

Of course, we in videogameland take our armchair lawyering seriously. At this very moment a legion of internet commenters descends upon us to explain Nintendo’s case on its behalf. A true copyright landlord must crush all acts of infringement, they explain, lest the magical lawyer faerie god come to strip them of their demesne and explode their top executives in a shower of legalistic viscera. You don’t want Shigeru Miyamoto to explode, do you? Clearly this fifty billion dollar corporation requires protection (from the kids making ‘Five Nights At Marios’ mashups in some wonderful little corner of the internet).

Nevermind the fact that Sonic fan works lead decades-long existences unfettered by that hedgehog’s corporate masters. Nevermind the fact that Sega releases its own officially-branded Sonic sequels every year, interleaved amongst the fan ones, yet has never once incurred the faerie god’s curse. Could it be that our legal code is less a set of rigid duties, and more an arcane spellbook empowering huge capitalist powers to pursue capitalism however they see fit? Surely not, the comment sections moan; surely Takashi Iizuka’s bloody reckoning is close at hand.

The reason we accept Nintendo’s rapacious monopolistic posturing under the guise of legal duty—the reason we’ve accepted its predatory bullshit for decades now, under a range of equally-crummy pretenses—is because such things are necessary to defend our magic circle. Just as we project meritocratic ideals upon the conditions of a videogame’s play, so too do we project them upon the conditions of production. We want to think of our favourite game makers as ‘the best’, rather than merely the richest; this impulse leads us never to voice glaringly obvious truths, such as “Super Mario Odyssey bought its way into the running for game of the year 2017.”

We are aware, on some level, that Nintendo subjects its employees to debilitating levels of crunch. We are aware of the dehumanizing conditions in hardware manufacturing facilities, and how their cost effectiveness is the direct product of global inequality. We must concede that Odyssey’s production budget was fattened by these various abuses; we must further recognize that in permitting such abuses to continue, we impose upon all game developers the burden of competing against them in our marketplace (as well as in game of the year debates). We must lastly recognize something that for gamers ought to be very intuitive: that the most common forms of competition involve replicating your opponent’s strategy, no matter how unsavoury or destructive that might be.

I believe we already know these things quite well; they should in no way come as a surprise. Yet as soon as the clock strikes ‘game of the year’, we draw a circle around our favourite products and discount our terrible knowledge as a collection of mere ‘externalities’. We praise whichever products are free of ‘jank’ (a distinction many publishers achieve using thousands of minimum wage QA labourers). We favour products that exhibit the highest degree of ‘polish’ (a clever little lampshade for the words ‘time’ and ‘money’). We even deign, on certain occasions, to reward certain indie projects whose devs spent their meager budgets cleverly (even though ‘meager’ in this case translates to at least a few hundred thousand dollars).

Had you read nothing in your life except a procession of ‘game of the year’ lists, you could be forgiven for believing that the world of videogames ends there. But Nintendo’s lawyers know otherwise, don’t they? Because beyond the AAAs and the indies live the denizens of gamejolt and itch; and with budgets approaching zero, mere cleverness can do them no good. All the ‘externalities’ we’ve been persuaded to discount serve to price these people out of the mainstream. We build our ‘game of the year’ competitions knowing they aren’t really invited; we know, but would be loathe to admit it. In any case, I don’t expect we particularly care. Odyssey is a pretty amazing videogame, right? Why fight for anything different when you can just play a series of increasingly-expensive sequels? Is that what you really want?

Boss Fight: The Mario of Marios

(Spoiler Warning: We’re talkin bout Super Mario Odyssey in this here world 3 boss fight.)

Suppose we inhabited some non-nightmare landscape, in which it actually did matter whether our game qualified as a bona fide satire of Super Mario Odyssey (and could therefore be published under fair use). It’s unclear at first how such a satire would look, since Nintendo prides itself on presenting utterly vacuous surface-level narratives.

This latest story is about Bowser hiring a team of forced marriage planners, which is a pretty fucked up thing to do. He believes that by erecting a cargo cult around the trappings of Christian wedding ceremonies he can avoid the unreckonable destruction Mario always reaps upon his Koopa clan. It’s kinda sad, and kinda tragic, and substantially gross. But he fails in the end and everybody winds up friends, so I guess this is all still appropriate for the kids? (As long as they don’t post fangames about it on the internet???)

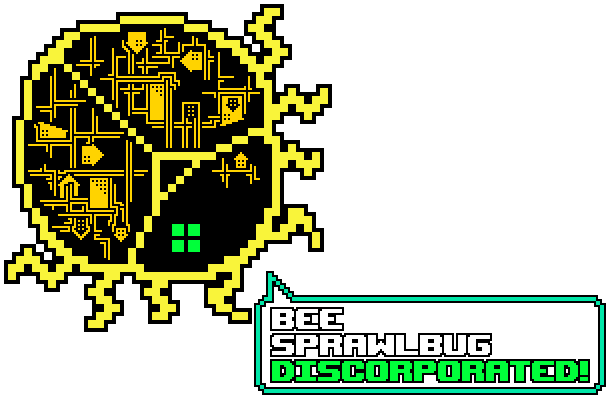

Dunking on Mario’s storyline is as entertaining as assembling game of the year lists, yet seldom qualifies as satire. This is because Mario’s politics do not lie within the magic circle, amidst the Mushroom Kingdom and the cake and all that other shit. They lie beyond it, in the business world and in the wider culture of videogames. To satirize Mario you must therefore blur, poke at or outright destroy the magical line dividing him from his parent company. And in fact, by scouring the regions of gamejolt yet unscorched by Nintendo’s lawyers (turns out they were a little lax with their google search terms) we can encounter a game that does so wonderfully: Super Plumber Bros.

In this game we don’t play as Mario himself; instead we inhabit his descendants, who profited handsomely from the family’s conquest of the Mushroom Kingdom and now live in Bowser’s former castles. We observe that the Toadstool monarchy has reduced the Koopa, Lakitu and Goomba peoples to states of squalor and near-extinction. Generation after generation, we watch the world and society slide into disrepair. In the end the kingdom collapses on itself, and we meet the Cthulu-esque monster god with whom Mario struck his faustian bargain: he exchanged his world’s future for the power to rule its present. (How else could he have decimated entire armies by himself?)

Plumber Bros succeeds as satire because it depicts a covetous organization exploiting its hegemonic rule over a territory it conquered long ago. Soon the game might also succeed as a work of prophecy! But not today, I’m afraid, since Super Mario Odyssey is as virile a descendant as any monarchy could hope to raise.

It’s an astonishingly wonderful product, isn’t it? Every inch of Odyssey is, in fact, as wonderful as human suffering could possibly permit. There are like 30 different species in this game for Mario to control by assaulting them with his hat; and every single one of these has an even more polished run cycle than Geralt of Rivia (including those gaudy-ass capital letters you march about until they spell ‘M A R I O’). You control these species by forcibly taking over their bodies, and usually you murder them after they’re no longer useful to you, but who cares! There are shiba inus in it. I think I’ve already mentioned the shiba inus.

The interesting thing is, once we start to blur the lines between the plumber and his parent company, it becomes unnecessary to think about satirizing him on a site like gamejolt; in truth the game does an excellent job of satirizing its own damn self.

Whereas Homer’s ancient Greek Odyssey presents us with the literal definition of a narrative epic, Mario’s adventure reads more like an Assyrian tableau. We watch him ‘liberate’ kingdom after kingdom in glorious fashion—that is, by making its inhabitants kill each other followed by themselves—yet everybody seems excited to watch this take place. The townsfolk pay him lip service even as they cower from his cap strikes. There is nothing for them to do except smile at him, and Mario is well aware of this; for Mario is the king of motherfucking kings. He has conquered the known world, and with this videogame, Super Mario Odyssey, he now offers us a set of tall tales regarding his legendary ‘kindness’. He is the oldest of all unreliable narrators: the victor writing history as he pleases. Beneath the sun of the Mushroom Empire, it is never not “Mario time”.

The most telling moment of all involves a festival in New Donk City during which Mario celebrates his thirty year run ‘n jump legacy by, well, running and jumping some more except in an amazingly expensive-to-produce way. The developers conduct an eye-popping, union-busting display of technical and design prowess, flattening Mario into pixel art and projecting him onto a skyscraper. He climbs up steel girders and leaps over barrels, aping his first appearance in a videogame, while the freakish human citydwellers congratulate him on his legacy. “Run, Mario! Jump, Mario! This is what we live for! This is the only reason why we exist!”

And Mario runs, and jumps, and climbs the city’s towers even as Daisy sings his praises. It’s a celebration of his supremacy, I suppose, over the world of digital entertainment. Thirty years, and Mario is still the best. Still he wins all the awards. Still his creators work themselves to death in the erection of monuments to his glory. Still his bands play jazz music, and their notes are the most palatable known to videogames. “Look on my works,” they sing to us, “and be judged.”

If you want to you can collect them to get power moons.

Epilogue

The unifying paradox underlying game culture’s consumer edifice—from big screen televisions to online shouting matches, and from comment section lawyering to ‘game of the year’ debates—is that our devotion to the appearance of fairness all but guarantees fairness’ absence.

The magic circle we inhabit is of course not made from magic; it is an ideological construct, which dictates what we can and cannot say regarding the products we consume. It is an ally to the capitalist interests who extract obscene quantities of profit from the game industry. It is simultaneously an enemy to the social justice movements who seek a truer state of equality for those participating in our culture. This is the effect our meritocracy has. It is, in fact, precisely what our meritocracy is for.

If you seek to escape a meritocracy such as this, you can do so by confounding its expectations. You can stop trying to win. You can stop recognizing winners. Yet those things by themselves can never free you. The most difficult step is convincing each of your peers to join you in your resistance; and that is why our meritocracy has persisted for as long as it has.

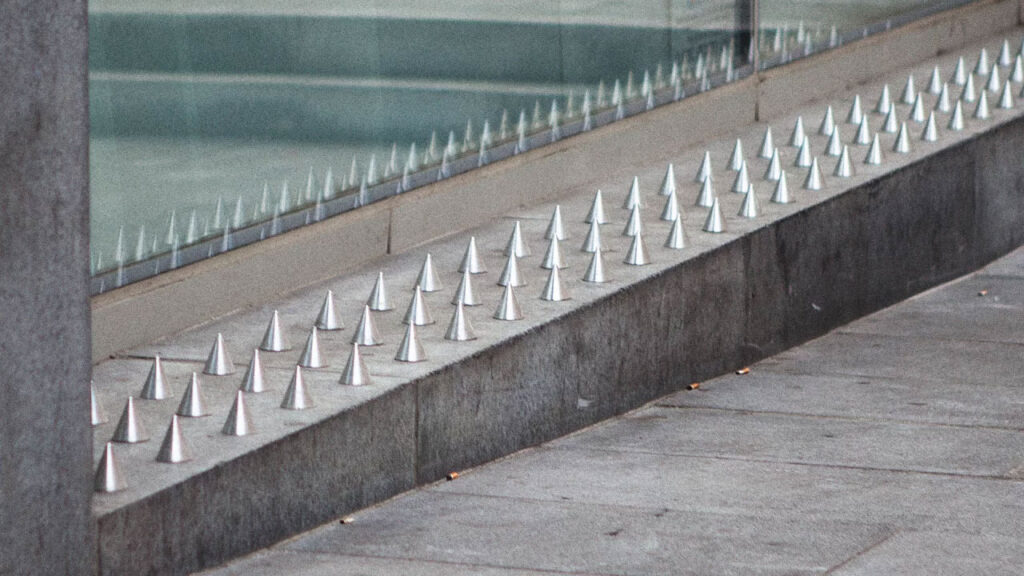

I think it’s okay to hold game of the year celebrations, and to prefer expensive work. I think it’s okay to buy TVs once in a while. But I don’t think it’s okay to abuse people during online competitive matches, nor to applaud every time you witness Nintendo installing anti-homeless spikes around its intellectual property. The predicament in which we find ourselves is that the former small indulgences establish preconditions for the latter indignities. They are all inextricably linked, like a massive Gordian Knot.

If you think I’m only here to spew a bunch of accusatory bullshit—or if you simply find yourself grousing over 99 cent microtransactions in Battlespace: Game War—I encourage you to watch carefully over the ensuing months as our industrial overlords methodically normalize the act of ‘paying to win’ (until we’re all shouting at our teammates for not having purchased the appropriate booster pack). Watch how the boundaries of the magic circle shift to accommodate the flow of wealth, rather than the ideals we believe we’re defending. Then return to this place for ‘game of the year’ 2020—during which some other Super Mario game will undoubtedly be a strong contender—and ask yourself whether this was all worth it.

Further Reading

Liz Ryerson’s “Fuck Mario”

Michael Lutz’ The Uncle Who Works For Nintendo

Eron Rauch’s “The Debate About Microtransactions Isn’t Really About Money At All”

Henrique Antero’s “Impaling Mario, Reversing Sonic”

Zolani Stewart’s “Where Sonic The Hedgehog Went Wrong”

Lana Polansky’s “Aluminum Smile”