In The Friend Zone is a Twine game by me that you can play (for free!) on itch.io.

My work on Friend Zone began with the game’s ending: a sort of prolonged joke riffing on a parable called “Before The Law” by a writer named Franz Kafka. Here are the parable’s opening lines:

Before The Law stands a doorkeeper. A man from the country comes to this doorkeeper, and requests admittance to The Law. But the doorkeeper says that he can’t grant him admittance now. The man thinks it over and then asks if he’ll be allowed to enter later. “It’s possible,” says the doorkeeper, “but not now.”

The man might overpower the doorkeeper if he wanted to, but behind this doorkeeper is another; behind that one is yet another, and so on. Each, if you believe what the doorkeeper says, is more powerful than the last. The man tries for years to talk his way in. He begs, he pleads; he bribes the doorkeeper with everything he owns. Nothing works.

Eventually the man is old and dying, and still he has not seen The Law. Then, as his death approaches, blinding light shoots from the doorway. He experiences an epiphany. All his thoughts and memories coalesce into a single shining question, which he puts forth to the doorkeeper: “Everyone strives to reach The Law,” says the man. “How does it happen, then, that in all these years no one but me has requested admittance?”

The doorkeeper tells him that no one else could have passed through this door. This door was made only for him.

I think the parable is about mistaking the subjective for the universal. The man imagined The Law within his own mind, so vividly that he mistook it for something outside himself: something tangible, something real. He further mistook it for something after which everyone strove, when in truth only he could strive after that which only he had imagined. The man desired something to seek, and not to feel alone in seeking it; and so, like a dog chasing its own tail, this man came to chase The Law.

My joke—what would become the conclusion of my Twine game—plays off the very same mistakes, though replacing “The Law” with “The Sex”. Before The Sex sits a casual acquaintance. A man from Reddit comes to this acquaintance and asks to gain admission to The Sex. He believes that as a man he must pursue some universal ideal of manhood: that this is his purpose and birthright, sought by him and all men like him. In truth he is more like a dog; though he hopes chasing tail will bring meaning to his life, the only tail he really chases is his own.

II

I always found Kafka funny as hell, which I think says a lot about me. Inevitably, each of his protagonists winds up prostrating their own dead body before some vast pretension—The Law is only one example—yet before that can happen, Kafka must create some waking nightmare that leads them towards their fate.

If you read much of his stuff—or play any of my videogames—you’ll be familiar with his go-to setup. It looks something like this. A man wakes up in his apartment one morning and is surprised to discover he’s turned into a monstrous, human-sized beetle. He jumps out of bed, thrashing his mandibles in a panic. He crushes three of his legs against the corner of the dresser, half by accident and half by frustration. It’s all ruined now, you see: he’s never going to make it to work on time!

It speaks to the human condition, this setup. Our biggest problems lie beyond us, so we resolve to focus on the smaller ones; our smaller problems are contingent on the big ones, so nothing ever really gets fixed. A giant beetle-man can do little except choose to go to work, yet a giant beetle-man cannot merely choose to go to work. He is trapped, and the cosmos must be laughing.

This cosmic deadlock is at the heart of all my favorite Kafka stories. To live is to become entangled with massive powers whose movements are incomprehensible; as they shift, like tectonic plates, we cannot help but stretch and splay. Often we become something monstrous. Inevitably we still have to go to work.

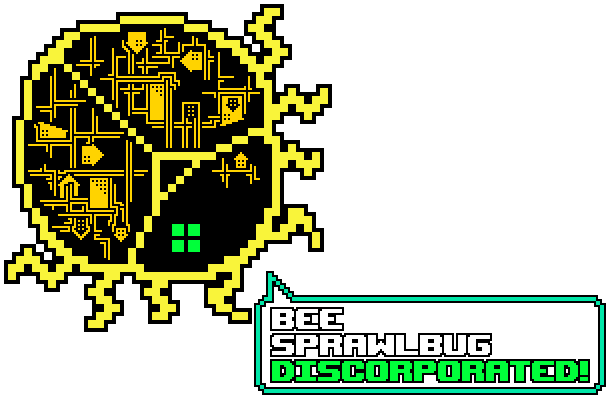

As I began building my “Before The Sex” parable into a full-fledged Twine story, I knew I needed all of these elements: a waking nightmare, a cosmic deadlock and maybe even a giant beetle. That’s how I became interested in ‘the friend zone’, and specifically in those people who view it as a prison where villainous succubi conspire to trap them. I sought a mythos for the Internet Man: that monstrous insect whose discontent leads him from Machiavellian snake oil sellers to an assortment of ill-fitting hats.

I wanted to account for his stretching and splaying: to find out how and why he was made. What caused him to believe in ‘the friend zone’ as a dungeon in which his enemies can lock him: to cast his acquaintances as “enemies” in the first place? Why does he feel inadequate for failing to sexually subjugate people, and jealous of those he believes to have succeeded in doing so? Why do I feel those same feelings, creeping on like gangrene?

To this end I conceived of a literal Friend Zone: some hellish parallel dimension to which each of a person’s various admirers becomes exiled. Over here, the Nice Guys™; over there, the Facebook Creepers; somewhere nearby, the murderous White Knight. Each prisoner plots their own unique means of escape; yet in true Kafka fashion, none shall succeed so long as they remain alive.

The first epiphany that comes to you when you’re trapped in the Friend Zone is that you inhabit an imaginary prison. Because your prison is imagined, your captor cannot be a real person: only something you’ve imagined them to be. Real people can never correspond to what your imagination seeks; and yet, what your imagination seeks can only reside in a real person. The cosmos must be laughing.

The second epiphany is that the person you’ve imagined can only be a reflection of you: a fragment, conjured up from what you think and feel. Those who dwell in the Friend Zone are not imprisoned by the object of their desire; they are imprisoned by desire itself, always entreating them to chase their own tail. The walls they build and occupy play host to a thousand doppelgangers, each wearing the mask of one person. They think they hate the person, but they hate only themselves. They think this person imprisoned them, but they must have imprisoned themselves.

The third epiphany is that you can escape from a real person or place, but never from its imaginary counterpart. It will follow you day and night. It will feed on your efforts to destroy it. It will wait outside the window to return, until your brain rots or you die. In time it will render you monstrous. You still have to go to work.

III

I’d heard at some point that “Before The Law” was part of a larger work: a novel called The Trial, which Kafka abandoned before ever completing a draft. Kafka died in relative obscurity ten years after writing it, known only for a handful of German-language short stories. His final joke was to request, in his will, that all his manuscripts be burned rather than published. He requested this of friend, admirer and prolific author Max Brod, who of course had already said he wasn’t going to burn anything. And so, instead of destroying Kafka’s manuscripts, Brod cobbled them into The Trial; the book went on to become world famous, flinging open Kafka’s door only after he’d perished in front of it. (I can think of nothing more Kafka-like than the notion of death imitating art.)

Every few years, some scholar publishes a new English translation of The Trial; several companies have now turned these into audiobooks, which I’ve come to prefer. I became curious and, after completing my work on Friend Zone, I decided to give this one a listen (a reading of the Breon Mitchell translation, whose work I quote throughout this piece). I was a little spooked to discover that the Twine game I’d just written bears an uncanny resemblance to the novel I’d never before read: that they are, in certain ways, the very same story.

Here is how The Trial begins. A banker named Josef K awakens in his boarding house bedroom one morning to discover that men have come to ‘arrest’ him. He is free to leave, of course—no one would deny him the freedom to go to work—yet the men inform K that his ‘trial’ has officially begun. Nobody ever specifies the crimes of which K stands accused, though Kafka does not depict him as strictly innocent. All they’ll say is that K must attend hearings at a ‘law court’ elsewhere in town.

We soon discover that the court resides in some liminal nightmare dimension. Its offices appear and vanish in the attics of unmarked tenement buildings, stretching their inner dimensions far beyond the limits of their exterior walls. All the novel’s exterior faces—the city streets, the rigid social hierarchies, all the badges and titles people wear—present a façade of immutable structural power. By contrast, the novel’s surreal interior faces resemble cancerous tumours made from the cells of this structural power: the same hierarchies, badges and titles reconfigured such that K can make no sense of them.

Here’s where the uncanny resemblance begins. Where The Trial’s banks and boarding houses resemble Kafka’s native Prague, The Friend Zone’s glassy towerscape resembles my native Vancouver. Yet in both texts, interior spaces seem to dissociate from their containers, forming labyrinthine breeding grounds for strange people and beliefs. Every character, in either story, has spent years plotting a way to escape the maze in which they’ve somehow found themselves; yet no plot ever succeeds, and so no one can provide either protagonist with genuine help (even though virtually everyone claims to offer it).

Readers of The Trial, like players of The Friend Zone, quickly realize that the protagonist should not merely weave from character to character hoping for some loophole that ends their ordeal; yet in true Kafka fashion, the texts permit our protagonists to do nothing except weave. K begins his story as a proud and merry cog in the city’s financial machine, believing wholeheartedly in his status and corresponding agency. Yet as his trial draws him from the exterior to the interior, his agency becomes supplanted by helplessness; the overbearingly-rational becomes supplanted by the intuitive; and as we shall see, duty becomes supplanted by desire.

Having read a bit of Kakfa previously, I was fully expecting The Trial to be surreal. What surprised me about it was K’s desperate, almost quixotic bearing towards the women of the novel. Despite his family’s grave warnings about how seriously he should take his trial—despite the fact that “The Trial” is written on the cover of the book—K spends the majority of the plot ignoring it so he might instead chase after a series of increasingly-phantasmal love interests. In the exterior world—before we enter the twisting law court—K busies himself by creeping on Miss Burstner, the woman staying in the room next to his. Since the men who ‘arrest’ him come in through Burstner’s room, K arranges to ‘chance upon her’ the following evening and ‘apologize’ for the disturbance of her things; this leads ultimately to K planting kisses all over her face while she responds, at best, with resignation.

Reading as I am in the year 2015, I must describe K’s behaviour as rapey; I must say he’d fit right in amongst the denizens of The Friend Zone, nestled snugly between the Nice Guys™ and the Creepers. It’s possible that his actions appeared dashing in the eyes of the book’s 1915 audience (as well as the eyes of the Internet Man). Regardless, the plot confirms for us that they were unwelcome and inappropriate, since Miss Burstner vanishes into the woodwork following the evening’s events. K makes several attempts to deliver her an apology for his ‘apology’ (a classic Internet Man manoeuvre), but her new roommate Miss Montag assures him she doesn’t wish to be reached.

As K’s trial progresses—and we move into the surreal interior spaces of the law court—his encounters veer from the uncomfortably rapey towards the dreamlike and absurd. It turns out most women of the court are inexplicably attracted to defendants such as K, but not solely to defendants such as K. Within mere hours of his arrival he becomes entangled with the court usher’s wife, who it turns out is also entangled with the examining magistrate and the law student who serves him. K’s encounter is cut short when the supernaturally-strong law student seizes the woman in one arm and, in the manner of Donkey Kong, carries her off to the magistrate’s office. She protests her apparent abduction even as she caresses the student’s face. It’s a psychoanalyst’s wet dream.

Later, K bails from a meeting with his nagging uncle, his useless lawyer and the important-for-no-reason ‘office director’ so that he might spend three hours fooling around with the lawyer’s nurse. The two carry on the worst-concealed affair in history even as K’s ‘case’ crumbles around his ears. Though he began his trial with arrogant bluster, vowing to expose a corrupt court system and assert his innocence for all to see, K is now fully enveloped in the twisting interior of the courthouse: trapped in an imaginary prison from which he can see no escape.

K winds up lost in a cathedral whose interior seems to wind on forever. There he meets a priest of the court (more specifically its “prison chaplain”). The priest is there to recount “Before The Law” to K, but not before berating him about his over-reliance on members of a certain gender. If you’ll permit me to quote at length:

“You seek too much outside help,” the priest said disapprovingly, “particularly from women. Haven’t you noticed that it isn’t true help?”

“Sometimes, often even, I’d have to say you’re right,” said K, “but not always. Women have great power. If I could get a few of the women I know to join forces and work for me, I could surely make it through. Particularly with this court, which consists almost entirely of skirt-chasers. Show the examining magistrate a woman, even at a distance, and he’ll knock over the courtroom table and defendant to get to her first.”

‘I must use these women to my advantage’, says the man who once ran right over his lawyer and uncle to get to one as soon as he could! The priest does not even respond to K’s outburst, preferring merely to bow his head; I think he might be embarrassed for K, who has long since become the monster of which he speaks.

From this point Kafka’s manuscript sort of trails off, skipping straight to the ending. We can fill in some scant details from his notes. The trial grows worse and worse. K’s career as a banker flatlines. Gradually he drifts into a fog of anxiety and fatigue.

It is during this period, in one of Kafka’s half-finished out-takes, that I encountered the uncanniest parallel of all between my Twine game and The Trial. In The Friend Zone, photographs serve as talismans to help prisoners remember their reason for being there: the way their ‘friend’ looked, acted and so on. These photos soon turn hostile, however; instead of depicting the object of their desire, the photos begin depicting monstrous versions of the prisoners themselves. Later the prisoners’ dreams come to function in precisely the same way: reverie becomes nightmare as images of the person they seek transform into frightening doppelgangers.

Kafka’s out-take, by comparison, depicts K napping on his sofa at the bank (he is too weary, most nights, to make the trip home right after work). He dreams he is seeking Miss Burstner amongst a crowd of other boarders, all glaring at him open-mouthed. He scans the crowd once, and fails to find her. He scans again and finds her this time, but her pose feels wrong; she stands with her arms around two other men, whom K recognizes from somewhere. He realizes he’s recalling a photograph he saw in her apartment the day of his ‘arrest’, and the realization shatters him. K cannot resolve the dissonance between the actual Miss Burstner, who occupies the apartment next to his, and the idea of Miss Burstner as he imagines her in his mind. He is trapped, hopelessly, between the exterior and interior world. As these worlds dissociate from one another, shifting like tectonic plates, K cannot help but stretch and splay. By this time he has become monstrous, his character torn in two halves. (Naturally, he still has to go to work.)

Once K’s trial has subsumed his entire life, it becomes obvious both to us and to him that its ‘verdict’ shall be his death. And so, like any good Kafka protagonist, K resolves to end the novel as a corpse prostrated before some vast pretension. It’s the only task at which K shall ever succeed.

The nature of this pretension—of K’s ultimate guilt or innocence—is famously difficult to encapsulate. People have read The Trial hundreds of ways: as Holocaust metaphor, as Freudian fantasy, as poster-child for existentialism and so on. My work on Friend Zone prompted me to read it as an elegy for the Internet Man, delivered 100 years before the fact. Like the Internet Man, K has exploited his station: lorded it above anyone he could, believing this to be his birthright and purpose. Like the Internet Man, K is too busy chasing tail to comprehend the shape of his crimes. His verdict is as much about big inscrutable forces as it is about a peculiar personal failing; it plays out neither with K’s complete consent nor fully against his will.

The Trial’s final sequence represents, I think, the best joke Kafka ever made. Two gentlemen come to K’s apartment again, precisely one year after his ‘arrest’. K has been expecting them. As they lead K out of town, he thinks he sees Miss Burstner walking far ahead of him; she disappears into an alley, but he refuses to turn his head and look after her. The gentlemen lead K to a stone quarry, where he is to die. As he lays prostrated on a stone slab, they pass a knife back and forth beneath his nose; they hope he will take it and use it to end his own life, but K refuses to do so. In the distance, K sees a spectre in a window. It might have been “a good person”, he thinks to himself. It might even have been “a friend”. Perhaps that was all K ever wanted?

The spectre opens its arms, seeming to offer an embrace. K, now held down by the throat, extends his own arms pathetically towards it. The object of his desire appears to him only now, when he cannot possibly reach it; The Law spreads itself wide even as his executioners plunge the knife into his chest. Seeing himself before it—seeing himself clearly, perhaps, for the first and last time—Josef K utters his final words: “Like a dog!”

Writes Kafka on the novel’s concluding line: “It seemed as though the shame was to outlive him.”