This is a story about why bad things happen.

The main character in this story is Nathalie Lawhead. Various secondary characters exist, many of whom we’ll just be calling “Boss Guy” (they’re different human beings, but those differences aren’t especially important). The other big character in this story is named Jeremy Soule.

This story is an essay, written in five parts labelled ‘Boss Guy ∅’ through ‘Boss Guy Ω’. Boss Guy ∅ seeks to be safe for anybody to read, & seeks to recognize Lawhead for some of their achievements over the years. Subsequent sections however call for a serious CONTENT WARNING, because these sections include serious discussions re: labour exploitation & sexual abuse/assault.

Boss Guy ∅: Flashpocalypse

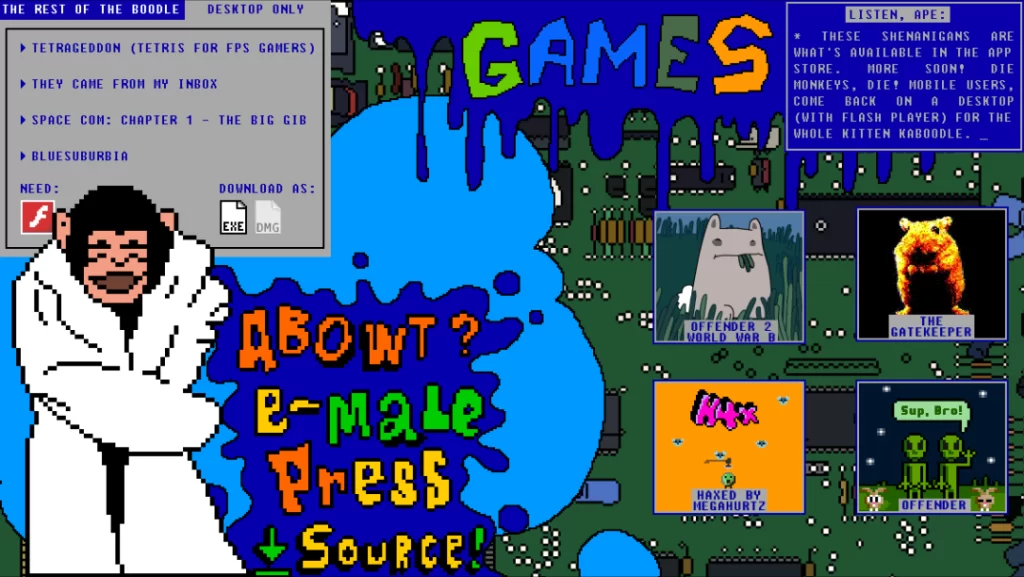

Nathalie Lawhead is a software maker whose projects are either artworks, or videogames, or else ‘game-like artworks’, or else ‘art-like gameworks’ (or else tools, or else virtual pets, or else ‘virtual tool pets’, or I could really go on forever here). As of 2020 Lawhead has won numerous prestigious awards, and in retrospect we can view them as one of our medium’s great artists beginning from the early ’00s.

I first met Lawhead around 2015, which was halfway through something called the ‘Flashpocalypse’. Both of us were computer programmers, & we’d both done poetic motion-y interactive media projects using a tool called Flash. In 2010 these projects became marked for execution (sentenced to death by Steve Jobs + his cronies, who sought to imprison our internet’s culture within their mobile phones).

On December 31, 2020, official corporate support for the Flash platform ended. Steve Jobs remains fucking dead, as he’ll continue being forever; yet Flash outlives him through the quasi-legal efforts of hacker conservationists.

Lawhead’s Flash projects were so good that to me they seemed to bend the fabric of spacetime; my stuff had been mediocre by comparison! Yet we shared the same one sky, I guess you could say. This was why Lawhead found my little Flash game to begin with, & why they shared kind words for it even years afterward. It meant a lot to me that someone like them paid attention, in a world where Boss Guy makes our attention so scarce.

The craft of programming game software involves many hundreds of Boss Guys, who imagine themselves to be in charge of everything and whose compliments don’t really matter.

Boss Guy gets to be ‘the master’ of our discipline, in that he gets to tell everyone what to do. & Boss Guy is ubiquitous across the working world; so really he gets to play ‘master’ over everything. Any job, of any sort, tends to involve people who’ll tell you what will happen (regardless whether your work actually benefits from their instructions).

Workers are required to be good at following instructions. Overseers, though, seldom need to be good at providing them. Most overseers suck, and barely try to hide it. Most have always sucked, even while accumulating promotion after promotion. Their only real job is ‘being in control’, which takes as many hours as they like & earns them as much salary as they figure it ought to.

Noone really benefits from overseers (even Boss Guy’s Boss Guy could usually save money just by firing his executives). Yet there is one certain kind of ‘master’ I feel young craftspeople do need. They need a master crafter—as in ‘crafter of many masterpieces’—from whom to inherit cool traditional knowledge re: tools, & how to wield them skillfully.

Boss Guy’s role within capitalism is to pay us money in exchange for telling us ‘what to make & how’; these concerns he shouts about all damn day + all damn night, so we don’t need master crafters to come shout about them more. Master crafters tell us something far more precious: What to value, & why we should value it.

Never ask a Boss Guy ‘what to value & why’, because he’ll never have useful words to share with you. He’ll only say something terrible, like “You should value implementing this player surveillance software!” or “You should value finding ways to replace yourself with a machine that I own!”

As crafters we are obligated to save Boss Guy from himself, & choose for him some values that aren’t just fake capitalist dreck. We’re here to build products that people actually like (rather than products Boss Guy shouts about all day), so we’re obligated to make some of our own tough critical choices. We choose what to find valuable in our software, & whose compliments matter to us the most, & whom to recognize for being real leaders within our shared creative tradition (a tradition Boss Guy claims to have “built from the ground up”, but to which he’s always been irrelevant).

For myself, and for my programming roots, I choose to recognize Lawhead in this way. There’s no other software that moves or operates or values things in the same way as theirs. When I build games I always hope to leave a visual effect like one of Lawhead’s, or some UI widget like Lawhead’s that expresses maybe too much personality. Nathalie Lawhead is a master programmer: We can think of them as ‘one of THE master programmers’. Lawhead is the protagonist of this story.

Boss Guy I: Moneyed Knights of Capital

The main antagonist of this story is Jeremy Soule, a serial rapist who once composed music for such videogame titles as The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind (allegedly).

What happens is that around 2008, Lawhead travels north to work for Boss Guy #1 here in the unceded traditional territories of the Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Soule is good friends with Boss Guy #1—since Soule is friends with many Boss Guys—and he first meets Lawhead while schmoozing at the office holiday party. Lawhead & Soule strike up a brief friendship; but Lawhead soon detects that Soule’s a five-alarm sorta ‘raging white guy nightmare creep’.

Lawhead needs this work, so Soule knows he’s found a good target. In practiced fashion he begins exploiting his influence over Boss Guy (issuing some threats to Lawhead along the lines of “It’s me or bust!”) and generally preventing Lawhead from moderating his access to their personal life.

You already know, or have likely guessed, that Soule rapes Lawhead while they’re trapped within their employment at Boss Guy #1’s game studio.

In a blog post from August of 2019, Lawhead calls out these guys’ past behaviour. Their post asks the same question I’m now asking, which is: Why? Why’d Soule do this to Lawhead & others? Why’d Boss Guy aid & abet it? Why’d our institutions all fail to be useful in the wake of Lawhead’s callout post? (Why’d companies like Kotaku act to make this situation worse?)

Here’s my basic contention about why: This all happened because the game industry is bad.

I don’t simply mean there are bad people working here, or that bad people mostly run things (though both these statements are accurate). I mean the game industry is MADE of bad: The drywall, two-by-fours and foundation are chemically composed from badness particles. Bad things happen here because “bad” is the main structural context in which all videogame commerce takes place.

This is easy to see about the game industry no matter what part of it you’re looking at, but it’s crushingly-apparent within Lawhead’s stories about Boss Guy. I recommend you read the specifics in Lawhead’s own words, from Lawhead’s own posts. I’ll summarize them here in brief, so we can sit together & explore the breadth/depth of Boss Guy’s bad acting.

Boss Guy #1 + associated overseers spend a lot of time gaslighting Lawhead about the quality of their work, stealing credit for any good idea whilst making setbacks appear to be Lawhead’s fault. Boss Guy bungles portions of Lawhead’s visa such that they can’t quit without risking deportation. He traps Lawhead, in other words, within an unsafe working environment he never intends to improve. Really he just uses all his power to make Lawhead crunch round the clock (to a degree that sounds punitive even by game industry standards).

I wanted to quip that Nathalie Lawhead could ‘out-design this Boss Guy in their sleep!’ but unfortunately this would be in poor taste (because it’s something that literally fucking happens). Boss Guy does compel Lawhead to fix his project for him whilst they struggle through a state of 95% incapacitation. Twice Lawhead winds up in an ambulance, speeding towards the Emergency Room. The project moves forward, because people such as Lawhead keep saving it; yet Boss Guy pretends as if Lawhead’s some huge point of failure that’s causing all these big slowdowns.

Boss Guy treats Lawhead the way I treat exhausted hockey players in EA Sports’ NHL 2020: Mashing SPEED BOOST as hard as I can, draining out every last stamina point, then whining frustratedly about ‘bugs!’ because the best character on my roster won’t stop suffering panic attacks. Taken as a whole, this might’ve been the least acceptable behaviour I ever saw documented in the game industry (if not for the fact that Lawhead’s second Boss Guy will later wind up being worse).

This is what I mean when I say the game industry is “made of bad”. I don’t mean to be vague, or poetic. I mean that in very official terms, this industry classified Boss Guy’s behaviour not as ‘abuse’ (nor as ‘violence’, nor as ‘evil’) but simply as 100% a legal + professional occurrence. It deliberately permitted Boss Guy + friends to get away with everything, & it deliberately permitted bad actions to maximize Boss Guy’s income at cost to Lawhead’s health.

Meanwhile any & all negative consequences remain somehow the exclusive property of the survivor: some bundle of traumas + secrets, to be gradually revealed over decades. A barrel of toxic chemicals that’s labelled ‘Property of Lawhead’ & can never legally be dumped.

I think it’s extremely shitty that our society & legal system make survivors responsible for carrying the entire burden of justice all the way to its finish line. From inception through completion—from suffering an attack all the way through public reprisal—basically we just leave survivors to do everything themselves, & call them ‘brave’ etc while permitting our peers to subvert them at every turn.

To justify this we’ll say “innocent until proven guilty”, or some other such phrase. Even when we know those words are simply a privilege people buy. Even when we see how our marginalized colleagues get ‘presumed guilty’, in thousands of ways, every fucking day. We still employ the phrases, & play out the arguments, & we eagerly accept each of Boss Guy’s cheerful deceptions regarding planet earth (pretending just for his sake it’s as friendly to us as it was to him).

The real phrase Boss Guy suggests to survivors of this stuff is something truly terrible, like “You’re unworthy of support until proving the privileged guy’s guilt”. This phrase doesn’t sound especially fair—if anything, reader, I’d call it kafkaesque—but that’s the real direction our processes actually point, & that’s the way our justice mechanisms actually work.

We can plainly see how nothing stood in place to safeguard Lawhead against bad actors: No hulking community org, no set of guilds/unions, no governing body (or lawyer, or bastard, or state employee or anyone). In 2009 there was nothing in place. As of 2020, there’s still nothing in place.

What does this say to us, about the structural composition of the videogame business? It says that in the end ‘bad actions’ are correct actions. Often they’re the MOST correct actions, & thus the only actions worth considering (for any overseer-type person, operating at any level of videogame commerce anywhere in the world).

Here then is my slightly-more-advanced contention about why this all happened: The game industry is made of bad because it structurally divides its participants into ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. It divides people MATERIALLY, we know, in that several assholes possess ludicrously-huge piles of wealth. Yet it also divides people ideologically (into attitudes about stuff like wealth).

To be a ‘winner’ you don’t have to be a Boss Guy. You don’t even have to be rich. You only need to wake up this morning & identify the shitshow before you as ‘100% normal’ (regardless what that situation is). Winners appreciate power, in that they cause power to appreciate: They view power/success as bankable commodities, which should climb ever-higher in the same fashion as house prices (power leading to more power, success leading to more success).

The Boss Guys we discuss here are winnerdom’s biggest faces: Moneyed and well-armored ‘knights of capital’, vying for investment from liegelords in California & questing to create ‘positive ROI’. Behind them though is a staff of non-commissioned winners that sucks just as bad (consisting of supervisors/leads/managers/executives). Then out in the vanguard are your coworker-type winners, who lack real power & often get screwed yet still dream of that 1% chance they’ll be able to benefit from nepotism.

All these people treat bad actions as normal actions, which is the essence of ‘acting like a total winner’. Any time you catch somebody doing that, you’ve caught them ‘winning’ at someone else’s expense. It doesn’t matter whether they personally took the bad action or not; it doesn’t matter who is officially holding the bag. ‘Winnerdom’ is really about attitudes.

Winnerdom is also non-monolithic, in that each winner expresses some D&D alignment apart from their basic feudal allegiance. Most winners regard themselves as ‘nice people’; most try inhibiting rape when that’s convenient. Only a few select assholes flaunt abject cruelty as the perfect solution for any workplace problem (yet said assholes exist in smaller numbers, and certainly are well-enough paid).

Every strain of winning counts as ‘100% completely a normal occurrence’, so nothing stands in place to stop any particular strain. The resulting status quo is that basically, anything goes: Even our nicest winners routinely screw non-white guys out of wages (while everybody around competes for olympic gold in ‘looking the other way’). The nicest winners we meet are still partial assholes; they just happen to be experts in practicing things like ‘plausible deniability’.

The opposite of winnerdom is loserdom, which is a state of complete & utter revulsion towards social hierarchy as a concept. Losing allows you to acknowledge simple truths: that things are 0% normal here, & that Boss Guy’s fucking lying. Losers never have to minimize Boss Guy’s abuses: They speak about them, loud enough to be heard, & they battle against the consequences of having spoken. Losers try to change the rules: They suggest new/exciting workplace policies, like “Don’t abuse your employees!” & “Don’t help Jeremy Soule get away with raping your employees!”

Lawhead confronts Boss Guy #1 with both these policy suggestions, which is the maximum Lawhead can do in their limited role at this company. Boss Guy rejects them both (because it wouldn’t be convenient), & then he wraps work on this project as if nothing really happened. The moment he ceases requiring Lawhead’s aid is the same moment Soule succeeds at duping this Boss Guy into turning on his best employee + cheating them out of their final invoice to the company (a well-respected company, or so the winners still say).

With this final touch Boss Guy finishes his “Portrait of a Complete Asshole”, so let’s imagine him exiting stage left. He goes off-stage to the left, to abuse whomever’s over there until whenever he retires (winners plan for us to simply put up with this until all of them have retired).

Boss Guy II: Resonatin’ for a Thousand

Let’s refocus on a new-ish Boss Guy—Boss Guy #2, who was at the same schmoozefest where Lawhead first encountered Soule. Picture him bumbling in from stage right, holding his ‘Boss Guy’ scepter & kinda waving it around without much of a clue.

This guy wants Lawhead to build his shit for him as well, but of course he promises it won’t be like last time: This time it’s mostly remote work, to be completed from Lawhead’s home in California. Lawhead feels 0% okay with letting Soule blackball them out of the videogame industry, & it seems the work being offered is guaranteed a bit safer; so Lawhead does what I would’ve done & accepts.

Boss Guy #2 proves himself an even worse boss than the previous one, but we don’t have space to enumerate every bad action this time out (you should read Lawhead’s posts). The executive summary is that Jeremy Soule attaches himself to this project similar to the last one (because he’s friends with Boss Guy #2 as well); & once again Soule’s presence exacerbates Boss Guy’s various mismanagements. Coworker-type winners get in on the act, & the crunchtime hits even worse, & Lawhead winds up cheated out of thousands in wages again.

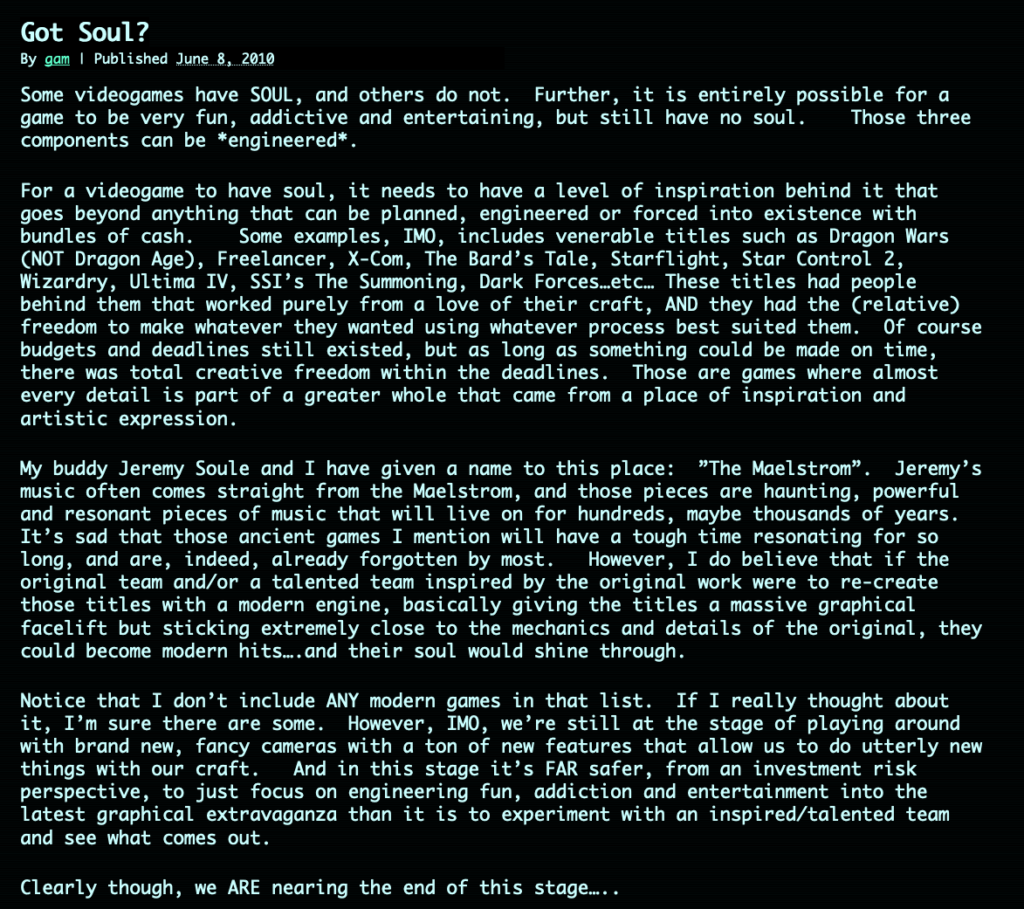

Lawhead introduces us to Boss Guy #2 through a blog post he once wrote, entitled “Got Soul?”

The first thing that strikes us regarding Boss Guy’s blog post is how incredibly annoying it is. It purports to answer the question ‘which videogames are the GOOD videogames?’, which to me is like asking which compass direction is ‘the BEST compass direction’. Boss Guy then selects an excruciatingly-annoying line of argument: What we might call induction via childhood.

Boss Guy estimates the goodest/most soul-having game projects by listing a ton of big commercial releases from big commercial genres he remembers enjoying when he was younger: “Dragon Wars (NOT Dragon Age), Freelancer, X-Com, The Bard’s Tale, Starflight, Star Control 2, Wizardry, Ultima IV, SSI’s The Summoning, Dark Forces” et cetera. (Can’t have ‘soul’ without a jetpack + a monster manual, know what I’m saying?)

Boss Guy cautions that soul cannot be “forced into existence with bundles of cash” (which is pretty funny because Dark Forces is a Star Wars game) then he regales us with some tedious lies re: how all his favourite gamemakers “worked purely for the love of their craft” whereas other gamemakers presumably did not & were greedy or whatever.

The most annoying part of the whole post is when Boss Guy introduces us to “The Maelstrom”, which is a space of pure creative potential from which soulful game projects originate. “The Maelstrom” is where we encounter Boss Guy’s conspicuous actual motive for writing this blog post in the first place: to organically ‘slip in there’ that he’s friends with successful person & fellow “The Maelstrom” resident Jeremy Soule.

Through understanding the power dynamic between these two winners, we can begin to imagine the private intellectual world of Boss Guy. We imagine that for Boss Guy, Soule’s praise is a valued commodity. Soule, in the same manner as disgraced R&B star R. Kelly, seems like someone who accomplishes great commercial feats. He seems to have all these cool industry connections, and he seems to have a bunch of industry leverage. He seems to have got what winners crave.

If Soule told you your project looked promising, well… wouldn’t he be in a great position to know? If he told you to do things to improve your odds of success, how strongly would you value that advice? And when you do follow the advice of a person like that, don’t they get more impressed with you & seem more invested in your project? Couldn’t their leverage conceivably become yours?

This is what we need to think about while we’re reading Lawhead’s account of how Soule behaves around the office. At one point he throws the most brilliantly-red flag in all of videogame history, which is something like: “I think it’s important to relocate Nathalie back here and make them live with me in my apartment [because their mom is a bad influence on them]!”

Boss Guy’s executive staff sorta goofs, & misses the redness of this flag; it becomes another thing for Boss Guy to ignore. He isn’t primed to consider Lawhead’s safety at all, which tells us something about how Boss Guy thinks. To him Lawhead’s just, y’know, like the Photoshop program he has open; he feels he can do whatever to just fix all that later (and maybe dodge paying for the license fee while he’s at it).

Soule, by contrast, appears very different. He’s no mere productivity tool; he’s a personal friend, & a personal advisor, who sits alongside Boss Guy on “The Maelstrom’s” HOA Board. We detect within Boss Guy’s blog post a bid to position himself as ‘similarly-successful’ to Soule, & ‘equally as important’ as Soule. Boss Guy believes in the transient property of surface-level details: Long as he stands next to more successful friends, he figures he’s bound to produce more successful opinions.

At one point Boss Guy asserts that Soule’s “haunting, powerful and resonant pieces of music” will “live on for hundreds, maybe thousands of years”. This is a pretty embarrassing flirtation in retrospect, because… well, I’m sorry Boss Guy but your rapey friend’s orchestral scores just aren’t that likely to become our century’s answer to the Parthenon, y’know what I’m saying? I don’t think we remember many famous pieces of music from the year 1020 A.D., and I don’t think we’ll care how many Morrowind discs still float on the Pacific come the year 3020. Basically I think we’ve caught Boss Guy talking straight out his ass in a bid to kiss Jeremy Soule’s.

It isn’t appropriate for Boss Guy to kiss R. Kelly-ish buttcheek (and certainly not as part of some awkward bid to improve his studio’s leverage). Yet winners would say that it’s all very normal, and it’s 100% legal + professional, and these ‘personal matters’ simply need to be kept ‘personal’.

Winners always aspire to keep matters ‘personal’—omitting the political side to equations such as this one—on account of how bad they look the moment someone takes up any political lens. Boss Guy’s definitely kissing R. Kelly-ish buttcheek in concert with a hundred other Boss Guys, who are all protecting + hyping the same one abuser guy for the same basic reason (a lust for success). It really does seem a lot like there’s some massive political problem here, looming over us like a poison cloud!

Losers wanna talk about it, but winners really don’t. Winners treat these matters as ‘personal friendship’, so nothing ever comes back to taint the corporate revenue stream (& the business entities owning all the assets never get close to being sued, & the related interests attached to those assets never lose out on profits, etc etc etc).

Regardless of whether you work in this industry as a junior tester or a CEO or even as a journalist, you will be asked to partake in this: You will be asked to take winner-y actions, & make unsavory friends, & perhaps protect some creepy asshole’s cleaned-up corpo revenue stream. Each of us senses the HUNGER emanating from beneath San Francisco: the pressure to work harder & longer & more, destroying ourselves chasing the completion of some ‘high quality experience’ within some ludicrously-impossible timeframe. The corp never tells us to literally abuse our colleagues (because that could get it sued); it mostly announces “I’M HUNGRY” and leaves humans to do the math.

Each of us, as individuals, are forced to choose every day: Is it 100% normal that our non-male coworker gets shit on again today, & we’re just gonna be garbage fucking winners about it? Or is that 0% normal today, & this is our cue to go have a decisive fight against the boss? Are we prepared to lose the fight today, sacrificing our job to some quieter winner-type asshole? Or shall we keep winning longer ourselves, and willfully participate some more in dividing Boss Guy’s benefits from our costs?

Of course it’s tempting to declare that we’d simply side with the underdog, and we simply wouldn’t accept unfairness, and we simply would abolish the crappy feudalistic power heap these dudes go skittering around on all day. We basically know that ‘winning’ is unvirtuous; in some circles it’s already a faux-pas to get caught agreeing with shit like Boss Guy’s blog post. Yet the fact is that fighting power is harder than becoming power’s vassal, & ‘to fight’ at all is much harder than simply challenging one’s superiors directly all the time (because you’ll quickly get subverted, & then fired, & maybe snubbed for years afterward).

Here’s my complicated contention about why this all happened. Every individual within the game industry stands internally divided between the realms of winnerdom and loserdom. We’re always torn between these, choosing how bad we’d like to personally act on any given day in exchange for something we want. Certain workers consistently act well; yet on balance most people don’t, so the corp always gets the majority of what it wants (mostly money) in some shitty manner that every industry expert agrees is 100% legal + professional.

In this world there’s a whole rich spectrum of reckless losers, cautious losers, cautious winners, conspicuous winners & even ‘temporarily-embarrassed winners’ like those tiresome gamers who shill for corporations on social media. Every individual fills many roles at once, & usually people play on both sides. Some make things better & some make things worse, yet by the end of the game we always find “the king stay the king”—or rather, ‘some fucking Boss Guy’ remains ‘some fucking Boss Guy’—& although we maybe swapped one gross man for another, the function of this chesspiece remains basically consistent.

This is why, at the end of Boss Guy 1 & 2’s various work-related atrocities, the state of our board is as objectionable as you could imagine. Boss Guy #2 wraps up his project and exits stage left (resolving, just like the first guy, not to change his studio at all). It’s 2011 now, & Lawhead’s been completing other people’s work for way too long. They’re still 95% in a state of incapacitation; yet still they carry this terrible burden to somehow bring justice against Soule (somehow all by themselves), & nobody anywhere seems very willing to help.

As for Soule, it’s 2011 so this is when Skyrim comes out. The dreaded Morrowind jingle returns, which gamers feel is awesome, & Mega Boss Guy over at Zenimax makes even more money than he’s ever gonna need. This period becomes the zenith/maximum of Soule’s personal success; he’ll be resonating for a thousand years for a couple more years after this.

What can we say to clarify this situation?

We can say a bunch of winners found lots of success using horrendous acts of abuse (but it can’t be traced back to them now). They exacerbated a huge labor crisis, in part by insisting the matter was ‘100% personal’ rather than being in any way political. They became very rich, & they became very powerful, & they proved themselves incapable of handling power even while accumulating as much of it as they could.

Corporations ran a system of incentives in order to make these abuses profitable (& profited handsomely themselves), yet without ever violating society’s de facto rules. Even Soule, who broke many important laws, probably received more from my government in funding than he ever heard from it re: sexual assault being a crime.

Whenever piles of capital exist that didn’t exist before, & the money looks way cleaner than what people actually did to obtain it, we know what to say. We say that money was laundered. We say these people laundered it. They plied a racket: a scheme, a scam, a con. They hurt a lot of people, & they laughed in the face of our ideals, & they figure they should just get away with everything.

We have special words for when seemingly-legit job opportunities crumble into wage theft + overwork + sexual assault. We sometimes call it “forced labour”, y’know what I’m saying? Yet Boss Guy doesn’t wanna think of things that way, so when it happens here we call it 100% legal + professional. Everybody is supposed to just ignore it and move on.

Boss Guy III: Crap Shillers Here

Many years pass between Lawhead’s experience back then and their choice to go public in 2019. Lots of things happen throughout that timespan, some of which we’ve discussed. Flash becomes marked for execution, & nearly finishes dying. The PlayStation 4 comes out, & then the PS4 Pro comes out. Most of the arctic ice shelves collapse.

Jeremy Soule spends this period torturing more people + contributing to more videogame/movie soundtracks (allegedly). He’s plugged into various winner networks that help him stay comfortable. Boss Guys at Zenimax + elsewhere grant ‘advantage from above’ to him, in ways we already mentioned; but he’s also enjoying a kind of ‘advantage from below’, which is his network of winners-by-proxy a.k.a. his fans (a.k.a. people who attach themselves to his brand name, & consider ‘success’ to be inalienable from Soule’s physical person).

Lawhead for their part makes the most of these years, despite it all, & spends them winning various awards + gaining attention from some cooler publications around videogames (e.g. Rock Paper Shotgun). By 2019 we can call Lawhead a household name, in that they’ve got ~1 ‘videogame household’ for every 1000 of Jeremy Soule’s.

Social media is a plane of corporate hell, & followings there are painful to acquire. Yet I believe that for Lawhead, building a following was 100% necessary in order to one day try stopping Soule. It’s true that Lawhead is “an American citizen!” & was the victim of a crime; it’s true that technically, they enjoy the right to things like ‘due process’ & ‘freedom of speech’ and all that. But none of these things are really Lawhead’s ‘rights’—they’re actually just privileges extended to rich assholes—so we know what really would’ve happened, had Lawhead stepped forward all by themself straight away back in 2009.

Powerful monsters would’ve tacitly endorsed Soule’s version of events; company legal departments would’ve denied all wrongdoing, painting Lawhead as a sketchy witness or some opportunistic liar. No one with the power to stop this would’ve done anything to stop this. The same old story plays out many times per day on our planet, & it’s demoralizing.

No one likes to admit that we live in a place where getting things you want depends first & foremost on having a ton of personal influence for yourself. We’d like to find comfort in modern notions about truth (that it carries judicial power in-itself, or that it somehow correlates to having freedom). We’d like ‘speaking the truth’ to be a process that brings justice to ALL survivors, regardless of their personal influence level.

We’d also like it to stop ALL abusers, regardless of their personal influence level; yet that just ain’t the case. ‘Speaking truth’ never achieves anything by itself, because knowledge in-itself is never power (Cersei Lannister reminds us that “POWER is power”). So in 2019, as journalists come sniffing around for juicy #metoo stories, we more or less find out how power enjoys responding to the truth.

Kotaku is the news org we deal with in this story, and another sort of antagonist to line up with the Boss Guys + Soule. Kotaku is basically a videogame media brand. If you’ve already processed your grief surrounding capitalism, you already think of that as something like “game advertising in the form of news”. If you haven’t, I guess we’ll say the company provides “videogame-related news as a service”.

Kotaku began back in 2004 as an effort by some game-magazine-type dudes to start commercially exploiting the internet (by shilling AAA videogames to incurious young men). They failed at that, amazingly, & so quickly broadened their focus (now shilling AAA videogames to ‘a somewhat-wider assortment of somewhat-younger people’). Before long they found themselves mining the life out of exciting internet communities like the blogosphere.

Kotaku sourced amazing blog-world talent e.g. Leigh Alexander, plus it got Tim Rogers from whichever tradition he’d say he comes from; then it padded things out with a stable of game-magazine-type dudes who probably seemed very relatable to Boss Guy at the time. It mushed its component styles together, creating a socially-engaged yet corporate-friendly news reporting pastiche. Always it relied upon stars like Alexander to offset the boringness of dudes like oh-just-name-one.

Recent years have seen Kotaku cultivate an interest in #metoo-type stories, using new & different writers to run the old Alexander-ish playbook (which involves bringing non-whiteguy angles to the forefront at whatever modest rate Boss Guy feels willing to accept). That’s why in 2019, when Lawhead’s blog posts emerge, it’s Kotaku stepping forward to provide official coverage for our story.

You already know, or have likely guessed, that Kotaku’s news piece will be a disaster. We’re gonna read it closely, like we did with Boss Guy #2’s blog; yet before we do that I think it’s important to gather some preliminary context. Let’s imagine the most justice-y outcome that could possibly have happened. What could justice look like here? What might it feel like? Which events take place?

This is what it looks like for me: Picture the company Zenimax, owner of Elder Scrolls, changing a bunch of its policies in response to explosive player outrage (because in MY dream world, gamers get outraged concerning real things). Picture future Skyrim ports omitting Soule’s Twelve Notes of The Apocalypse, cuz in the end it’s not so important to play a jingle for money. Picture non-whiteguys contributing music in that piece’s stead, & building really satisfying alternatives! Picture those people actually getting paid the proper amount.

Picture a society that understands complex issues re: separating art from the artist, & so accepts Soule’s presence within game history as a point of bare fact (while rejecting the notion that his fingerprints need to stay all over things forever). Picture a corporate wave of divestment from Jeremy Soule, such that after a while he stops receiving whatever kickbacks are currently paid out. Picture a series of lawsuits, and maybe even some art grants. (My city loves imagining itself as ‘a center for game development’, but in order to actually be that its Boss Guys would need to return some of what they steal.)

Kotaku’s forthcoming news piece is not responsible for accomplishing any of these objectives I imagined; at least, not directly. It’s only supposed to start the ball rolling here: maybe towards more articles, or more survivors coming forward, or an investigation, or anything like that. Instead what happens is Kotaku stops the ball dead (by putting some winners on the case who ignore the majority of the story I’ve been telling you), & basically a number of people do their best to fuck up the entire thing.

There’s a special phrase in game journalism for when you fuck up the entire thing: You say ‘it was 100% legal + professional!’, then you go deposit your salary.

This time around our Boss Guy is Stephen Totilo (the longtime editor-in-chief over at Kotaku dot com). Boss Guy is here to deliver his audience exactly what it expects: a story about ‘the famous creative man we’re supposed to know and love, except he rapes powerless women!’

Rather than accurately depicting Lawhead’s personality & stature within the game community, this piece conceals 99% of that stuff. It includes nothing re: Lawhead’s achievements, the way I attempt to do at the beginning of this essay. It includes nothing re: their work at the border of games/art, or their multitude of projects that get featured in cultural events all around the world. It fails to use any of the easily-googleable narratives other writers developed for introducing this person to their readers.

This piece reduces Lawhead to the nigh-anonymity of being a “veteran developer”, which to me is like calling Frida Kahlo “a veteran art teacher”. It mentions their project Tetrageddon, which you might once have read about on Rock Paper Shotgun; but Kotaku itself seldom covers that stuff (because there’s seldom been convenient money in covering it, and Kotaku is an org that values convenience).

For contrast, here’s how the piece describes Soule: “one of the most celebrated game soundtrack composers of all time, having helmed the soundtracks for The Elder Scrolls, Guild Wars, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and dozens of other games over the past two decades.”

This line reads like part of a puff piece for Jeremy Soule, & that’s probably because Kotaku is accustomed to writing puff pieces for winners such as him. Cursory searching on that website reveals 2 lifetime posts tagged “Nathalie Lawhead” but 583 tagged “The Elder Scrolls”; & really, it doesn’t take a journo degree to understand what that says. It says Boss Guy + staff writer awarded all the space in their piece to some asshole in whom they’d already invested too much coverage, & already spent too much time hyping, & already helped earn too much money for his jingles.

If you’re an editor-in-chief or really any kind of Boss Guy, you always wield the privilege of dictating your intentions after the fact. Boss Guy #3 here can choose any excuse for why this article fucks up Lawhead’s intro: Maybe it needed to be ‘really focused on the issue at hand!’, or maybe it needed to be ‘unbiased from the PoV of our readers!’ or something along those lines. Okay then, Boss Guy: What’s our justification for this Jeremy Soule sentence? Why is it I’ve been made to read all about the soundtracks mister rapist guy “helmed” in his career (allegedly)?

Boss Guy will note how in the past, Kotaku threw this or that jab towards Soule’s Kickstarter scam. He’ll mention schoolyard games the site’s long played against Zenimax over access to unreleased game products (an inconvenience, which did little to inhibit the publishing of 583 “Elder Scrolls” posts). Certainly he’ll try emphasizing how ‘space ceded to the rapist guy’ is subtly different from endorsement! And when pressed to justify his poor conduct towards interview subjects, he’ll operate off the 100% legal + professional-sounding maxim that ‘silence gives consent’.

It’s still a huge problem, though, that the winners in our media kissed Soule’s butt even while accusing him of rape. This is the same thing that happened with the media + R. Kelly, & it went on for decades, & it was 100% shameful.

There aren’t that many differences between ‘buying a lottery ticket’ and ‘working with some journalist on a #metoo story calling out your very-famous abuser’. Yet here’s one important difference: Lotto companies print the odds of winning, while journalists simply lie.

Could be this story they’re building ‘has legs’, and thus there’s a 1/10 chance of their piece leading into follow-up benefits (added reporting, new criminal investigations etc). Probably though the odds of toppling some very-famous abuser are more like one in a million, right? By concealing and/or distorting this fact, journalists enact a laundering scheme: They frequently sell salacious details re: people’s personal lives, but seldom seriously invest in the political effort to topple abusive assholes.

Boss Guy always remains free to dictate intentions after the fact, so in these matters he’ll execute a very popular manoeuvre I call ‘Option A’. First he’ll fuck somebody over; then he’ll loudly pretend he’d always been trying to help (“mistakes were made!” he’ll tend to proclaim). Option A, writ large across our society, is the base operating mode of global capitalism.

‘Option B’ is the cooler one, wherein Boss Guy actually sticks some neck out + actually takes risk + actually helps people who are lower than him on the grand ladder of capital.

Realizing that here, within our story, would have been very demanding for anyone. Firstly it’d demand an utterly amazing sort of staff writer to compose the right words: someone to manage all the official legal stuff (while also doing risky/unpopular advocacy for small communities (while also being an upstanding figure within those communities (who’d probably already know Nathalie Lawhead, since by 2019 they’re an extremely-visible ambassador for smaller videogame stuff worldwide))). You’d need somebody to run the real Alexander playbook; you’d basically need someone like Alexander.

Let’s call it a testament to Kotaku that for the majority of its existence—up until ~2020, when their good writers all quit in droves—there’d always been someone on staff who met these daunting criteria!

The piece we’ve been discussing was unfortunately written by Cecilia D’Anastasio (who never met the criteria for ‘Option B’, yet reputedly did meet certain criteria around narcissism over the course of her Kotaku career).

When Boss Guy chooses to send her, it’s a little like he’s cancelling ‘Option B’ in advance; & indeed, the writing we see come out of this is thoroughly unconscionable (I learned more from Boss Guy #2 concerning “The Maelstrom” than anyone learned from D’Anastasio concerning Nathalie Lawhead).

What would’ve been great, given this rather-mercenary staff writer, is some kind of sympathetic audience: One that already agrees with the points she needed to make, & already follows Lawhead’s career, & already appreciates alternative-type videogames, & thus already is inclined to side with Lawhead as a survivor (over some fucking creep who composed a jingle one time around 2002).

Boss Guy failed to build this audience over the years because he was too busy chasing higher-convenience money for the corp, & this aspect of the debacle is hardly D’Anastasio’s fault. We know the game press’ primary mandate has always been to promote big products at the expense of community projects: It’s always been invested in reprinting bullshit excuses why incumbent winner-type assholes deserve to keep winning forever. D’Anastasio’s article accomplishes Kotaku’s baseline goals, & it’s no big surprise because that is what Boss Guy hired her to do.

Three or four weeks after publication, it becomes apparent how Kotaku’s sketchy news piece racked up higher damage against Lawhead than it ever could’ve racked against Soule (which is a bad outcome that resulted from numerous bad actions, though I gather journalists treat it as ‘normal’). Kotaku-reading creeps have begun mobbing Lawhead’s inbox, emboldened by Kotaku’s emphasis on sexual detail; so Lawhead, having already been strategically deprived of much recourse, asks our third Boss Guy to just take the thing offline.

Instead of doing that, Boss Guy + D’Anastasio take turns explaining the 100% legal + professional reasons why the article has to stay up forever (because journalism), & his staff can mess with master programmers/rape survivors at will (because journalism), & soon they’ve concluded that Lawhead’s just too stupid to comprehend the full rigours of ‘journalistic ethics’.

I too must be far too stupid; because like Lawhead, I can’t really agree that it was ‘ethical’ to kiss this R. Kelly-ish guy’s ass.

I’ve talked to people from the media world about this, & they always claim something impossible: that game news websites aren’t out here to shill industry crap. They claim their work to be separate: They claim some meaningful barrier exists between media verticals & the owners of that product they wrote 583 articles discussing. They wave around some ethics ur-text they stole from real news, & they try to call me stupid for challenging them; but I call this an effort to realize ‘Option A’ on behalf of all their peers.

Please understand: I don’t feel it’s wrong to shill the industry’s crap. I come to this conversation as a seasoned crap-shiller, having programmed in the industry for years. I’ve shilled crap just a little; I’ve shilled crap quite a lot. But I’ve yet to get through a project without being ordered to shill crap, because the game industry is made of bad & thus ‘crap shilling’ is foundational to existence here.

Everybody’s shilling crap: I’m shilling crap, you’re shilling crap, and the game reporting sites in particular are obviously shilling crap. These ‘might-as-well-be launch parties’ they throw, coinciding with every hyped AAA release, are obscene. The fake-ass corporate hashtags fill every timeline, & screenshots from the presskit cover every damn inch of every damn page of every damn media feed in the world (crowding out everything else). In my experience these practices make smalltime game-makers feel terrible. I believe every project deserves to be celebrated, in some form or way; but 99% of them never are, by anybody, & this is one thing that happens when venues fill their job openings with winners who live and die by ‘Option A’.

People love ‘media launch parties’, and most smaller-time creators I know would cherish one of those for the rest of their lives (even if it lasted 3 hours, & even if it featured a 2.5-star review). But most game reporting sites never grant parties like that to the smaller-time releases, and I think it’s due to their rather-dramatic dependence on having a rather-extreme volume of eyeballs flowing across their capital accumulators each day. They’re addicted, in other words, to an endless procession of ‘big-ass hit videogames’ flooding through social media and juicing their analytics—they need it even more than the game publishers need it—which means whenever these websites throw some launch party for a videogame, they’re really just ‘partying as a service’. They’re partying for Boss Guy, & they’re partying to get conveniently paid, & their readers are attending not as honored guests but rather as human appetizers for the feasting corporations.

In the old days these places would even throw mini-Nuremberg rallies, streaming Boss Guy’s banners down both sides of the webpage so you couldn’t look anywhere in your community without seeing some white guy + his gun.

Seems to me our news media is so dependent on riding waves of hype (which are so over-financed and draw so much gamer eyeball) that everyone’s basically stuck in an alternate form of vassalhood to bigtime industry Boss Guy. We know this kind of vassalhood is 100% legal + professional; we know people aren’t being “bought off”, or whatever Gamergater thing. But it’s still an influence laundering scheme, & everybody can see this.

The people journalists exploit—the smaller time game-makers populating #metoo stories for example—they’re not separate from you. They’re not animals in cages to be Gawker’d at for a convenient bit of salary. The people here are all equals, & like it or not our asses really are all in the same one boat. Don’t insult me by framing up some bullshit metanarrative about the good y’all are doing in some war of “Reporters + Consumers vs. Boss Guy’s Embargo Date”. Save that shit for the gamers, alright? Boss Guy is turning humans into sausage over here, & all the real professionals need to stop helping him get away with it.

The game we’re really playing is “Boss Guy vs. everyone”, and I know y’all knew this already. Every person here needs to start respecting a certain code. Never treat somebody the way Boss Guy wants you to treat them! That’s just obvious. If you’re sent to our community to do some dirty job, notify us about your asshole Boss Guy’s asshole motives (just like I do whenever I give talks to uni kids & explain all the stuff from this essay). Be responsible to the people around you, not to the Boss Guys above you.

I assure you, reader: I truly had no desire to author this pile of agony. I waited more than a year, drafting & deleting, hoping for qualified journo-type media people to step up. I waited respectfully for the supposed adults in this room to justify their own influence, & y’know what? Nobody did. Nobody with power tried to make anything happen for my colleague, & Jeremy Soule + Boss Guys remain largely uncontested (in my city no less). So here I am, with my dark & damning words. D’Anastasio may have kissed one specific R. Kelly-ish ass in 2019 with help from a lot of her associates, but winnerdom in general did worse (informers + entertainers, influencers, game executives, industry organizations etc): All you folks managed to lick boot effusively for a year.

I’m sorry, but because I waited y’all earn the complimentary upgrade from “ass kissing” into “bootlicking”. My peers within game-making watched you bootlick all day for a year. My game-playing friends watched you bootlick all day for a year. My non-commercial game crit friends watched you bootlick all day for a year. We see what work you’re achieving on Boss Guy’s behalf, & of course it’s gonna be as legal + professional as you designate it to be. But when it comes to real notions of ‘being independent’ & ‘having credibility’, I gotta ask: Who do you think you’re fooling, besides each other?

Listen reader: This website is free. Actually free (as in libre, not gratis). This essay isn’t designed to juice some corporate revenue stream, so I don’t need to waste half of it pandering to the rapey guy’s audience. I don’t need subsequent justifications for having profited off readers’ latent misogyny, and I certainly do not need some bowl of fancy loopholes to explain why I’m allowed to wantonly denigrate master programmers/rape survivors.

I realize this might be a strange concept, but I’m actually accountable for the sentences I write here (cuz I’m not a Boss Guy, & regular people don’t enjoy the power of dictating their intentions after the fact). I will edit this website the moment it seems kind to begin doing so; & I promise, I’ll eat these nasty words as soon as they cease being accurate. Make me eat my words, goddamnit! I hate having to call people bootlickers, it’s tacky.

Let me formally invite you to come live a few of your stated ideals, & join us here on Team Loser. We demand you make + enact plans to prevent your peers from aiding + abetting Boss Guy’s acts of torture. We demand you bring an end to the practice of editors + marketers dispatching winners who raid our community in search of personal prestige. We demand you take responsibility for the negative consequences of your conspicuous laundering. At the very least, you must dispense with these tedious lies re: what your real motives + incentives are.

Everyone can see you. I don’t know why you’re making me say this, but seriously: Your emperor’s fucking naked. I’m tired of this.

I know you hate the idea of any person ever treating you the same way game studio execs treat their workers in your stories. But we’re all just crap shillers here, y’know what I’m saying? Which means unfortunately, this is your community too.

Boss Guy Ω

Throughout 2020 Lawhead adopted a practice of tweeting @kotaku on a near-daily basis. The thing Lawhead wants is very precious: They want “accountability”.

It’s easy to sort of huff at this, and wonder loudly what “accountability” even means. It’s easy to view this from a ‘just the facts’ perspective. It’s easy to note how D’Anastasio is gone (fleeing to go work at a different influence laundering service), & that firing Totilo wouldn’t offer any leverage over the asshole winners that replace him. It’s very easy to bring up the fact that none of these Boss Guys/reporters are actually Jeremy Soule.

I think services like Twitter have limited the public’s imagination re: how restorative justice can look. The way things appear there, it feels like we’re choosing between two bad options (either “let’s boycott something!? [ehh I dunno]” or “let’s scapegoat somebody!? [err maybe not]”).

Boss Guy at Kotaku is a pretty crafty one, who knows what to do when you get caught laundering. He knows that in about a year’s time, half the site’s audience will simply churn over (filtering in a bunch of new readers who don’t remember this story at all). He’s shopping for a fresh crop of writers who’ll avoid this subject forever; & he’s keeping Kotaku silent, knowing that the corporate ‘hunker down’ move tends to always work. Right now he’s waiting for we ‘barbarians at the gate’ to run out of energy, or become too bored, or maybe all turn on each other while disputing the logic of potential product boycotts.

The longer the silence, the more hopeless things seem to look; that’s the benefit you get from maintaining a vast corporate silence. You paint a picture like the laundering all finished years ago: some vague saga from way in the past, such that no one today could take any reparative action that made any sense. Corporate silence signals to you that the story you’ve read here already passed into legend; it summons some force to now drag you into the future (with nothing good ever happening along the way).

I don’t think the real picture is as hopeless as the silence makes it look. I also don’t think we’re out here just to pick between boycotts & scapegoats. I think that stuff is an elaborate fiction.

This thing our corporations present to us as “the internet”—social media, video sites, news sites et cetera—does not offer us a view into our real historical present that we really can act to fix. What the internet actually offers us is a view into the prospective near future, which Boss Guy has ‘curated’ using bits & pieces of the shit he currently owns.

In this prospective impending reality—let’s call it “the corporate future nightmare world”—the winners & losers within our stories have all been predetermined. The conversations we experience are more like opportunities to list cool/awful reasons why it’s excellent/terrible the winners already won (or the losers already lost).

I believe corporate future is the reason game companies treat crap shilling with the same urgency as vaccine research: the reason we crunch, & steal, & pointlessly break every human limit. Everything seems to get justified by some rich asshole’s impending plan to get richer; yet 99% of the time, Boss Guy fails at his plan anyway (& we only get 1% of the good he promised us for going along).

There’s only one method for staying the Boss Guy as long as Kotaku’s has, y’know what I’m saying? He’ll say different, & he gets to dictate intentions as he likes; but the way you actually achieve that is by hedging all your bets so the rapey guy’s downfall needn’t necessarily effect your associates’ friends’ revenue streams. We saw this go on around R. Kelly for decades (media people continuing to ‘objectively cover’ his music + salacious details of his personal life, long after they needed to be reaching for some figurative knives).

Nobody benefits from ‘coverage’ in the form of more gamer-facing spectacle; we don’t actually need more winners hanging out trying to maintain their brand. What we need is losers, a.k.a. solidarity.

We might be living in a big grand story, but we aren’t living in a news piece. This isn’t about who has the best take/does the best look; this is still real life. I know humans who worked at these companies before finding out what happened there. I myself took a job interview at one, way back in the middle 2010s. They offered me a contract, but chose to undercut my existing salary/benefits by a somewhat insulting margin; so I declined that offer and narrowly missed working there (because white guys like me can always dodge a bullet from that particular smoking gun).

It’s very stressful to imagine working under one of my colleague’s abusers due to some corporate secrecy + implicit threats they imposed; I think this feeling has been stressful for everybody around here. None of these events, places or personalities are really in the past. All of it is present. It lives where we live. So for me it’s not so helpful when people choose to focus on the spectacle layer, & act as the ‘bad look police’ (e.g. scrutinizing Lawhead’s social media moves, as if this thing were their exclusive property).

We knew this was going to be a difficult process, for everyone. Everyone’s supposed to be having a difficult time. That feeling of never knowing what to do next—that sense of this problem sucking air out from the room, & sucking the space out of many conversations—that’s a normal part of this (& it was preordained when Soule began laundering abuse; not when Lawhead began speaking out).

I think the right attitude to have here is that Lawhead’s gonna do what they’re gonna do (& we, in the meantime, must do better than being postage-stamp-sized human heads that spectate + scream at the world). The relevant question for us is: What are we gonna do to help? How are we gonna try to protect people? You, me, & the rest of the people around here. This is our responsibility too, and we are failing at our side of it.

I wish we were in the phase of this story where the rapey guy falls down in defeat, & the bluechecks all squabble over who steals credit, & the losers can finally have some unit of measurable progress to wave in Boss Guy’s face. But we aren’t really there yet, because the ‘winners’ around here aren’t ready for that yet. They wanna sell more fake futures instead of showing solidarity, so that means the phase we’re in is still truth + reconciliation.

It’s a cold fact that no one really launders/wins ‘forever’. No one’s bullshit will resonate for a thousand more years. It isn’t a question of whether we acknowledge e.g.: this Kotaku piece’s bad intentions. It’s just a question of when. It’s a good thing to take care of soon, & a small part of what we ultimately need to do. “Accountability” includes telling the whole truth, and that could look as simple as acknowledging that your company duped you into taking a flagrant ‘bad action’ as part of running the machinery within a broken system.

We need to resolve these things faster, because we know they’re still rolling new Boss Guys off the lot every moment we speak. These folks plan to lie & cheat & steal + sometimes rape their way across our whole community. We know it’s necessary for everybody to act in opposition.

I don’t have a silver bullet solution that’s guaranteed to achieve good outcomes while hurting no one. But I think it’s something like: Everybody here (everybody who’s made it to this paragraph) holds a little puzzle piece that fits into our overall way forward. I think you should read Lawhead’s essays, which are a valuable account of life in this industry & a crucial part of the overall solution. I think you should read Marina Ayano Kittaka’s “Divest from the Video Games Industry!”, which is another puzzle piece that summarizes our community’s many ongoing efforts to discorporate (it means “to leave your body”).

Long ago—maybe halfway through the Flashpocalypse—I wrote inside a project of mine that “everybody’s gotta do something”. I still think it’s true. I don’t get to find out for you what it is you’re gonna do to help (I am continuously trying to find out what I’m gonna do to help). But we’re all obligated to try getting onto ‘the right side of history’ here, because one day history is gonna burn this rapey composer man + this world’s useless Boss Guys to cinders.

Look at the rooms you’ve chosen to stand in; reflect on the passing of your body into history with each expended heartbeat. You’ll run out of chances to change where you’re standing, probably sooner than you think. Are you sure you’re in the right place?

Further Reading

Nathalie Lawhead’s “calling out my rapist” as well as “my followup post”

Marina Ayano Kittaka’s “Divest from the Video Games Industry!”

Grace In The Machine’s “We Need to Talk About Games Journalism”

Natalie Degraffinried’s “Some Thoughts About A Website With A Fake Japanese Name”

Rock Paper Shotgun’s “Tetrageddon Games” Tag

Suggested Soundtrack

M.I.A’s “Hussel”

Leigh Alexander’s “This is Why We Video Gaming”

The Mothers of Invention’s “Absolutely Free”