Memory Sequence I: The Prodigal Child

In my favourite scene from Time Warner Incorporated’s The Dark Knight (2008), a lawyer named Harvey Dent presents us with his infamous dilemma: Either die a hero, or live long enough to see yourself become the villain. This is a false choice—at least in our boy Batman’s case—because under no circumstances would Time Warner Incorporated ever permit this character to die. Their shareholders implore them to pile sequel upon reboot upon ‘shared cinematic universe’ upon yet more sequels, indefinitely, until the heat death of the universe (or at least the destruction of capitalism). Batman is legally unkillable. He is therefore the villain by default.

The corporate future nightmare world affords us ‘freedom’ either to consume or avoid characters such as Batman, which we must exercise during every moment of our lives. In my country it costs twelve dollars to watch Batman at a cinema, which is always an option for tech workers such as myself. Avoiding him is an option for everyone on earth, and carries a financial cost of zero dollars (plus a social cost tech workers may never have considered). Yet the true freedom in play here—that is, the option to make and market a movie such as The Dark Knight—costs 185 million dollars (and due to licensing agreements is possessed exclusively by corps such as Time Warner Incorporated).

If we decide to abandon our passivity and exert an active dislike towards Time Warner films (imagine: disliking Justice League) we are encouraged to oppose them by ‘voting with our wallets’. Never mind the fact that Time Warner is their own legal person with a wallet half the size of Gotham City; never mind the personal and ecological costs of pouring 180 million dollars into a sinkhole just to verify that it’s a sinkhole. Somehow we’re supposed to organize a big political ‘voting with our wallets’ movement, uniting tens of millions of wallets across forty different countries + numerous different languages, in order to bargain against Hollywood over issues of product design.

The only reason ‘free market’ types even present this crap to us is that they know it in their hearts to be impossible. No process or technology exists that might facilitate it, and the resources with which to build one reside in entities who would oppose its creation. In truth we can only sit and grumble, watching an inconceivable number of strangers surrender an inconceivable sum of wealth to an inconceivably complex bureaucracy sheltering a handful of inconceivably rich oligarchs. This is the actual purpose of these films; this is the actual content they present. Time Warner is not here to be a bastion of consumer democracy. They’re more like a fleet of fishing vessels, casting the biggest possible net in search of the best possible return. And food—as we humans well know—doesn’t get to vote in elections.

As a species, I think we must concede that our progeny have surpassed us. We fashioned these corps to be a synthesis of all our great myths: part person, part nation-state, part factory, part god. We bequeathed to them everything we once sought for ourselves. We gave them fairness; we gave them security. We gave them a clear sense of purpose, which is something we ourselves never possessed. We even managed to grant them eternal life. Now it is they who enjoy the privilege of walking the earth and making decisions concerning the things they observe.

Corporations are the truest citizens of this world. Insofar as it remains conceivable in any fashion, it is conceivable only to them.

This is how I console myself every time I see a tabloid at my local supermarket: “I’m watching American Media Inc. exploit one of their long term revenue streams.” It’s a positive and sense-making perspective, isn’t it? Look at the happy little corp, frolicking about, accumulating capital and living its best life! I try to ignore that I’m seeing sexualized photos of a six year old girl who was murdered in the ‘90s, yet lives on against her & other people’s will as a sort of subscription-based sideshow. I ignore these thoughts because I’m incapable of understanding them. I don’t understand why the tabloid in front of me exists. I don’t understand why I can’t prevent its existence. The source of its power is inconceivable to me. It’s beyond my biological limits.

By roleplaying as a corporation—adopting their language, and a rosy view towards their life purpose—I can momentarily detach from the kaleidoscopic tragedy that would otherwise consume my field of view. It’s a popular and effective coping mechanism! So popular, in fact, that many tend to mistake it for being a social role (assuming that by using corpo words they have joined ‘the adults in the room’). How often do we take to the internet and address corporations as if they’re listening? We make smart video essays surveying the business of Sonic the Hedgehog. We throw stupid social media rants about how “female ghostbusters will NEVER SELL.” We are hopeful, perhaps, that by speaking the corps’ language back at them we might somehow be treated as their equal. But we aren’t their equal. Not in power, not in cleverness, not in anything about which they care. We are merely the cells in their bodies: their labourers, their food source, their vector for expansion. We are their precursor race.

Memory Sequence II: The Enigma of Big Data Fault

We currently live (or should I say, we currently die) in a geopolitical epoch called the anthropocene. It is an era in which we have more data at our disposal than ever before, yet it remains completely impossible to understand why anything happens.

In the entertainment industry we can overcome this fundamental limitation, helping corps like Time Warner accumulate vast sums of money despite never conceiving good proof of how/why their successful products actually succeeded. We achieve this rather dubious feat using a concept called Big Data.

Here’s how it works. The audience for entertainment numbers in the billions these days, which is a completely inconceivable number. Luckily we’ve got all these complicated machines that let us probe the population for hits and misses. We start by trying whatever idea the boss comes up with. Then we check our ‘key performance indicators’ (money made/attention paid/compulsive behaviours inlaid). If the numbers look bad, we eventually stop. If the numbers look good, we make incremental adjustments to nudge our rate of return closer to its local maximum. Batman, JonBenét Ramsey and… *squints at notes*… pregnant Elsa from Frozen are, for inconceivable reasons, proven to be what the people want.

The certainty of profit amidst the utter absence of understanding is fascinating to me. It’s like a 1970s sci-fi story crossed with a Junji Ito comic. One day there’s this quippy Shakespearean philosopher guy named James T. Kirk in your television. Maybe you think he’s cool; maybe you think he’s not. But your opinion in itself is worth very close to nothing (because you aren’t twenty million people, and you don’t have 180 million dollars).

Viacom’s shareholders implore them to feed this ‘James T. Kirk’ into a Kirk-shaped crevice within their mass market optimization device. As he slides his way into the crevice—down and down and down what turns out to be a long chute—its dimensions become incrementally less Kirk-shaped. Those pulpy love affairs he fell into once or twice distend into insatiable lust. His self-assured demeanor elongates until he’s a bossy, ill-informed blowhard who always turns out to be right.

Eventually some grotesquely-misshapen ‘reboot’ emerges from an opening on the machine’s opposite side. Out slithers Zap Brannigan—or rather, Chris Pine cosplaying as Zap Brannigan—bumbling and swashbuckling and screaming continuously from his injuries. We watch with fascination as he “DRR! DRR! DRR!”s his way towards the nearest set of human-compatible genitals. Then we lock him in a cage and set about designing new merchandise.

Do you judge this Kirk preferable to the one who first entered the machine? Is this a refreshing or exciting new direction for you? Do you think you might’ve wanted something different? You could explore these questions on a culture blog, and fifty emails later it might earn you a cool twenty bucks. But from Viacom’s perspective the answer is ‘who fucking cares’, because their film earned twice its production budget and that lets them type “franchise” into a series of quarterly earnings reports. There are no further opinions worth considering; there is no discussion to be had. The data is here, and the data is us, and its exploitation for profit (that is, our exploitation for profit) remains enshrined within every law of the marketplace.

This is why the folks among us who rely on the salve of entertainment to distract from the terror of existing (a popular and effective coping mechanism!) must watch, over and over again, while our favourite mass-market work drifts off in inconceivable directions. Many learn to preserve their dignity by bearing it with a sense of wry wit (“smile when you eat the gagh!”). Others turn to giant pointless essays, and/or works of Marxist literature! A true consumerist, however, surrenders their dignity wholesale in exchange for a fictional pact of ‘loyalty to the fans’. They treat the hollow drone of marketers as if it were legal and binding. They issue endless threats of boycott, expecting some invisible hand to enforce such things on their behalf. They embody, in a hundred different ways, the tragic misconception that this world was made for them.

Memory Sequence Omega: Pipelineworld

Batfleck and Nu-Kirk are easy targets for me; those characters were never dear to my heart. Yet I am not without sentiment! I still feel a pang of lament every November, when a videogame publisher named Ubisoft ships the next Assassin’s Creed.

Critical consensus holds that the second game in the series—Assassin’s Creed II, which was a round plastic disc you had to slam into an “Xbox 360″—was the apex of the AssCreed franchise. Here at CFNW, however, we believe in shitting upon the critical consensus every chance we get. That’s why, when I buy blockbuster videogames, I’m not looking for that Metacritic 90. I don’t want a safe bet; I certainly don’t want respectability. I want the wild, the strange, the borderline unpalatable! As such my favourite AssCreed has to be the very first one, from way back in 2007.

This was a period in history just before the global ascendance of smartphones as the medium of choice for playing videogames. In places like Europe and America it was still all about buying bigger, faster computers to indulge our unexamined fetish for violence; so on platforms such as the Xbox 360, big corporate publishers tended to dominate the scene.

The Grand Theft Auto franchise had garnered enormous wealth by bringing the ‘open world adventure’ concept to twenty million new customers, though nobody could say why specifically these games blew up. Was it firing an Uzi out the driver-side window of an off-brand Bugatti? Video poker games at casinos? Ritualized violence against digital stand-ins for sex workers? No one knew for sure, but a number of publishers were prepared to make large bets.

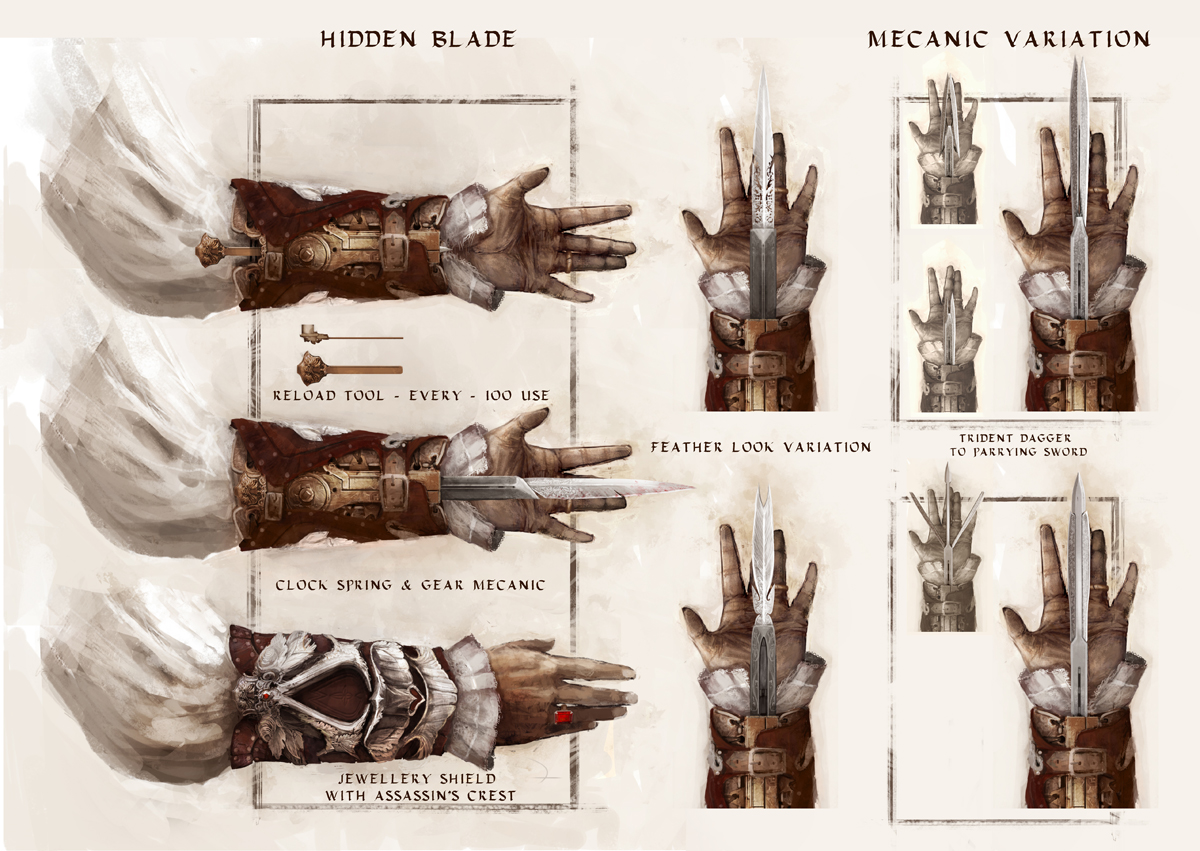

In the end it would be Ubisoft who joined Batman, JonBenét and Grand Theft Auto in the pantheon of market ubiquity (pregnant Elsa being still a few years out). They’d do so in unconventional fashion: with a Syrian hero murdering unscrupulous Christian-aligned dickbags using his cool-ass concealable wristblade.

The studio had to build this game from scratch, which entails a whole lot of guesswork in terms of project planning; and we can tell simply by playing it how difficult the guesses must have been. On one hand the cities are crammed with many repeats of the same exact four subplots. On another, the spaces between these cities are huge, and empty, and accentuated solely by mood: all lonely ruined pillars and isolated guard towers, cloaked in a post-process haze. Compromises took place here.

It’s traditional in the consumer press to view such compromises as errors, or as deficiencies. Yet for me they’re what make AssCreed so unique in comparison to its successors. I’m sure the boss requested a landfill’s worth of ‘open world’ blandness: one hundred and eighty plot cul-de-sacs, ninety hours of collectible crap, some gift-wrapped Skinner boxes and so forth. (“It’s got what gamers crave!”) But this team couldn’t have had the resources to accomplish all that. They couldn’t rely on the contemporary strategy of blasting their world out a fire hose into the hypothetical player’s gawping mouth; they could only afford to suggest the scale of the world they’re here to represent, and the result is something rather like an impressionist painting.

We play as Altaïr, a heroic & stoic parkour guy who must haunt the many rooftops of Acre, Damascus and Jerusalem. Each city contains numerous themed districts (one that’s real poor, another that’s real rich and so forth). Production constraints left little variety to spread between these districts, yet it works out all the better: We gain the sense of a vast urban Escher-scape that stretches unto the horizon.

Whereas contemporary ‘open world’ shit builds its structures out of Velcro such that players can scale skyscrapers in an instant, this game does something rather different. Altaïr climbs as quick as a monkey under the right conditions; yet the cities he inhabits are only partially cooperative. Their streets are narrow, the handholds irregularly distributed. The buildings feel towering despite standing only two stories tall. It requires a bit of effort to reach the rooftops, offering safety to whomever makes the trip.

When Altaïr jumps from a rooftop, it feels like actually jumping from a rooftop. He must trade the safety he accumulated during his climb for the momentary element of surprise. It’s risky, and daring, and fun.

Content Warning: The following passage makes reference to sexual violence.

Altaïr’s enemies, I must note, are often some shitty soldier-cops trying to maim an innocent person. Sometimes this is a scholar, or a priest. Other times it’s a woman; and after Altaïr rescues her, it comes out that the soldier-cops were planning murder and/or rape (“They did not say what they wanted from me… but I saw the darkness in their eyes”). On one hand I find this to be a shlocky and inconsiderate narrative trope. On the other it’s entirely consistent with the documented behaviour of both soldiers and police officers from every historical era (including our own). The game repeats these encounters many times, making them seem like some strange recurrent fantasy. It’s grim, and bizarrely voyeuristic, and about what you can expect out of blockbuster videogames in 2007.

Being a parkour guy, Altaïr’s main job is to kill the shitty soldier-cops. He can do it all sorts of ways, and sometimes even by mistake. Yet the obvious approach involves wristblading one of the men before he knows any kind of fight has started. It’s a sudden, violent, dramatic reversal of power. One moment he’s standing there with his chin up in that quintessential ‘cop’ sort of way: projecting the aesthetic of invincible tyranny and doing whatever he pleases. The next he is a sack of meat sagging to the ground, not even worthy of the game’s glowy ‘currently-selected bad guy’ effect. (Hard to say this soldier-cop didn’t deserve it.)

Taking these four distinctive qualities all together—the sparse in-between landscapes, the labyrinthine cities, the dreamlike repetition and that wristblade through the gullet of state power—we get a good glimpse into what makes AssCreed remarkable. It’s a place through which I recall traveling even ten years after the fact; and when I spin it up again I’m still fascinated by the way it all feels. Yet here comes the punchline: I, Brendan, am a total statistical outlier! The vast majority of people who might encounter this game in their lives will not respond to it as I did (which is why it only got 81 on Metacritic). What this means is that Ubisoft is fully justified in ignoring me.

AssCreed sold something like ten million copies, which was well beyond anyone’s expectations. This was excellent news for Ubisoft—and terrible news for Brendan—because it transformed the game from some curious little gem into one of the industry’s most popular franchises. Now Ubisoft was free to do what all capitalist factory-gods dream of: expanding production capacity indefinitely, until hardly anyone can compete.

You see, Ubisoft did not bet on the ‘open world’ concept just to move ten million units of one single videogame from the year 2007. Of greater importance was the matter of sequels, and specifically how many goddamn assets it takes to produce sequels of this scope. Smaller videogame concepts—think Tetris, for example—were the stuff of pitiful humans. Lots of people could make Tetris (and as mobile games would reiterate, lots of others could then clone it). Open world games were different: They demanded something inhuman, and inconceivably-huge. They demanded what game makers call an ‘asset production pipeline’: armies of modelers and artists and designers and more, plus a hideous pile of software for piping it all onto an Xbox 360 through a circular plastic disc.

The benefit of owning such a pipeline was that, so long as the audience valued scale and resolution above all other concerns, Ubisoft could pour their considerable wealth directly into a machine for hit products. They could move ten million units every year, all the while growing their pipeline so that few could match their rate of production.

There would be some collateral damage, as all pipelines tend to create: The moodiness, the cohesion, the utter specificity of that first game in the series could never scale to inhuman proportions. Fortunately this was of no importance at all to anyone except Brendan. ‘Gamer’ is the most corporatist of consumer classes. They take to expensive production techniques the way moths take to a streetlamp (producing similar environmental consequences). Throw these people 5000 extra polygons, and they’ll all but declare you the pope.

(If perchance you find yourself taken aback by my casual use of ‘pipeline’ to describe artworks rather than oil spills, please remember which medium we’re talking about here. The videogame industry’s ‘standard practices’ are a legalized framework of exploitative bullshit including but not limited to: wage theft in the name of passion, ‘work for hire’ contracts designed to silo any/all knowledge within undying corporate estates, and shifty trade schools built to convert student loans into labourers at a pace that is altogether absurd. It burns through human components in only a handful of years, so the ranks need constant replacing. At worst, industry labour resembles bloodless trench warfare; at best, it’s more like being an Oompa Loompa.)

Ubisoft tripled the workforce of its Montreal studio for the development of AssCreed 2 and, in so doing, dispensed immediately with the endless recurring fantasies and winding dreamscapes. The crusades were now over (I would’ve said “thank god” but y’know); instead of Altaïr we’d meet the smarming & disarming Ezio, who runs around stabbing Borgias in sumptuous Renaissance Italy. It’s a cool game! At one point you kick some dudes off a rooftop while flying in a steampunk-looking hang glider made by your friend Leonardo Da Vinci? Anyway, gamers regard this as one of the finest videogame masterpieces of its era (one might say the “Mona Lisa” of videogames, although Ezio would not date her until later in the series).

Those sparse in-between spaces I adored in AssCreed 1 became paved over—a little more with each new game—using hundreds and then thousands of mass-producible ‘points of interest’. Remember that scene in Fargo where Carl buries a briefcase in the snow by the side of the road? It’s like that, except the opposite: There’s only one single square meter of terrain in which you couldn’t find $920,000 just sort of lying around. I made numerous attempts to renew my love of AssCreed via this fetid bog of interest points, yet I never could manage to do it. It just drains all the mystery out of the world.

Gradually the scope of production expanded beyond Montreal, incorporating more and more Ubisoft satellites until, by their fourth production, they owned enough content factories to commence their annualized release cycle! Now every November could be an Ass-stravaganza, moving ~10 million units of ‘open world gameplay’ in some new and exotic locale. Assassins in Turkey! Assassins in America! Assassins in the Caribbean! They’re everywhere you want to be.

When the pipeline started showing signs of strain (sometime during the French Revolution), Ubisoft made the altogether unusual choice to slow production down. They awarded their studios a full extra year (!) of development time, hoping to pack in more production and restore their dipping sales numbers. (A fun exercise for the reader: Google “asscreed unity bugs” to discover uncomfortable truths about realtime computer graphics algorithms.) The resultant product was AssCreed: Origins, released during hellish/frightful 2017.

This game stars an Egyptian guy named Bayek, who is something of a ‘mad dad’/former soldier-cop. Every AssCreed sequel finds exciting new ways to insult me, and Bayek’s ‘revenge cop’ archetype does qualify to some extent. Yet even more insulting are the game’s Velcro-like surfaces. Ptolemaic Egypt is awash with massive structures, and they’re all very pleasant to behold; the problem though is that Bayek can scale any given surface at speeds that would shame a helicopter. In this way the world’s shape becomes irrelevant to whatever’s taking place (the world’s size/orientation/permeability are simply too uniform, so every situation is basically the same).

Ten years ago these spaces were painstakingly-composed: The buildings would’ve offered more contrast, and for me provided more excitement when travelling between them. Today I guess we could say they are painstakingly-manufactured: Every building’s purpose is the same, and that purpose is to provide uniformly-efficient transport between one interest point and another (such that not even the royal palace dares stand between Bayek and his loot crate).

Gone just the same are any traces of that old reversal in power—the dramatic conversion from soldier-cop into meat—which established the aesthetic and politics of the origin Assassin’s Creed. At one point my ‘level 11’ Bayek tried stabbing a ‘level 13’ soldier-cop in the throat. Bayek enjoyed a rather obvious tactical advantage: his victim lay asleep in bed, just snoozing their life away. I had snuck into the bedroom, earning my advantage painstakingly; it was really very important for him to die a quiet death, being that I was surrounded by his unsuspecting allies. Instead what happened is they rose from their slumber like some old-world Jason Voorhees, two thirds of a health bar still remaining. They absorbed a few more weapon strikes, as if Bayek were wielding plastic toys. Then they slashed our hero to death with one awkward, glancing swing.

To me this was a shocking betrayal of the wristblade: cold and definitive evidence that Bayek is no ‘assassin’ of any kind. Instead he’s just a collection of stats and experience bars, like you’d find in a hundred other games. The numbers all inch higher by small increments, administering little bursts of amusement as if I were strapped to an IV bag laced with painkillers. It’s nothing like the videogame I remember from ’07; yet it’s numbing, and euphoric, and as we proudly declare in videogames sometimes: ‘a truly excellent waste of time!’

Finally, I suppose, the franchise succeeded in the task Ubisoft assigned it. It became the apotheosis of popular art: not so much an impressionist painting as a photo you might find framed at IKEA. Here at last are all 180 unique plot cul-de-sacs! Here are all ninety hours of the promised collectible crap! Here sit the infinite gift-wrapped Skinner boxes, which Ubisoft counts like sheep as it retires to its quarterly slumber. This game has ‘bumped the slump’ just as Ubisoft planned, lining up to move ~10 million more units (plus the revenue from in-game purchases!) by maybe the middle of this year. The pipeline keeps on churning, reader: and despite some complications, the results have been nothing short of spectacular. I hate this game. Loathe this game. Can’t hardly stand this game. It is a perfect product, in other words, and I congratulate its authors. Bayek is the hero we deserve.

Many of AssCreed’s competitors still operate in an outmoded fashion. Take Naughty Dog, for instance, and their franchise Uncharted. They’ll spend many long years making the best game they can—obtaining near-universal praise and earning that coveted 95+ Metacritic rating—all so they can sell about the same as one year’s worth of AssCreed. (It’s remarkable how important these review scores used to be!)

For many of Naughty dog’s fans, this remains a religious and political issue. Being the one Big Datum not hidden behind walls of nondisclosure, ‘review scores’ permit gamers to roleplay as the corp: to view the world as Naughty Dog might, and concieve some kind of fairness within the things that happen. That’s why those people still lose their shit when some stray review score happens to deviate from the mean: It threatens their very identity, since the supposed ‘truth’ of the metascore had long been their one sad/fake peephole into the corporate future.

Game publishers (being inhuman nightmare entities) were once known to rob their employees by cancelling overtime-related ‘bonus pay’ in response to poor review scores. They viewed such scores like one of those ‘KPI’ things: a magical statistic whose attunement led to money, and which employees could easily manipulate if only they stayed late enough and peed enough blood. The review score’s power was upheld on both sides: consumers and financiers touching fingers at the veil between earth and heaven, ensuring all labour stayed sublimely in a state of exploitation.

I don’t know whether Ubisoft imposed many of such agreements on the teams behind AssCreed. But when their executives do speak publicly about such matters, they speak of different KPIs altogether: day-over-day retention, hours spent in-game, IAP purchase rates and so forth. These are tricks they gleaned from social/mobile games, where the notion that anyone would care about ‘critical reviews’ has always been a joke. Ubisoft is adopting the corporate-style KPI: proprietary and secretive, such that there’s no legal way for competitors (nor consumers) to see what’s happening. This is where the industry is headed (where it’s already been, as far as the mobile game giants are concerned). As such, the metascore is doomed.

What are gamers to do with the knowledge that Ubisoft’s IKEA print outsells Uncharted’s Metacritic 95? They can only watch in horror as a cherished metanarrative—the mythical ‘objective review score’ as predictor of success—crumbles gradually around their ears. There will be no more window into the lives of game corporations. There will be no illusion of a marketplace founded on respect. Their lives will be rendered into data—the way mobile players’ lives always have been—until their range of vision is limited to what the game platform shows them, and their basic role as ‘player’ is to populate someone else’s database. They will grow to hate new sequels as much as I hate the present ones, squealing and crying about ‘loyalty to the fans’. I will watch them do it, if I live long enough, and I’ll probably laugh my head off like a fuckin’ Watchmen character.

What can I say, reader? The future makes villains of us all.

Further Reading

Erin Horáková’s “Kirk Drift”

Jason Schreier’s “Metacritic Matters: How Review Scores Hurt Video Games”

Austin Walker’s “Assassin’s Creed Origins Does A Terrible Job Introducing Its World”