I attended IndieCade for the first time this year!

My friend ceMelusine and I had grown tired of watching all our twitter friends have fun at game conferences without us. And so, right after missing GDC last March (for the twenty-fifth consecutive year) we resolved to fly down from Vancouver and see what IndieCade was about.

I didn’t get everything I hoped to from LA, as is usually the case when my surroundings require me to schmooze; I am often shy, cold and awkward around new people. Nonetheless, I am pleased to report that the conference yielded many memorable moments and a few resonant themes. I thought I would document them here as a sort of travelogue through the great state of small videogames.

Influences

The conference opened with a talk between David O’Reilly and Pendleton Ward, who teamed up to recount anecdotes from the animation industry while speaking obliquely about their artistic processes and influences. In doing so they upheld a time-honoured artistic tradition of obliqueness: Although we fans feel compelled to seek common threads through the work of our favourite creators, no one wants to pigeon-hole their own stuff as a mere recapitulation of someone else’s. As the talk segued into a Q&A period I steeled myself for the usual assortment of glib questions from which only glib answers can result. But then Andi McClure stoop up!

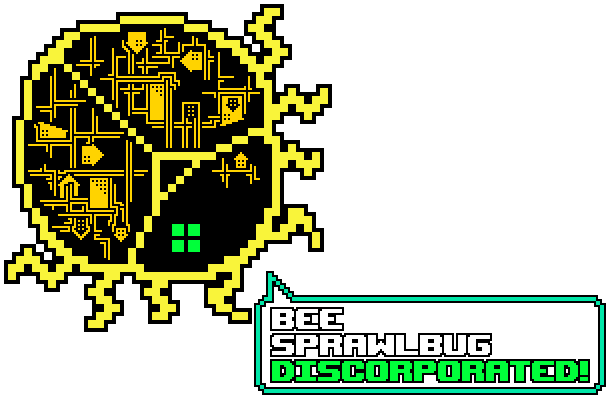

Andi McClure is a wizard whose BECOME A GREAT ARTIST IN JUST 10 SECONDS (co-authored with Michael Brough) was for me the highlight of Night Games. She began her question for O’Reilly by noting that while the majority of 3d animation work tends to look very homogeneous, O’Reilly’s projects always manage to look different from everything else in the field (even from his previous 3d projects). She went on to ask how he achieves that uniqueness and whether he explicitly plans for it.

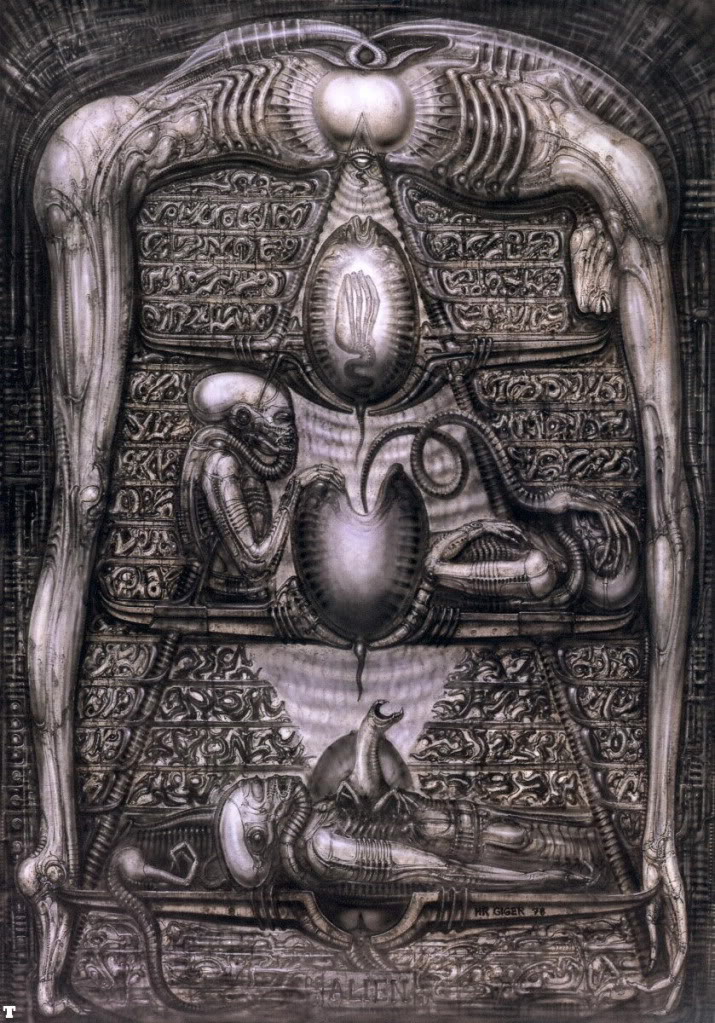

O’Reilly responded that while the majority of 3d animators view their tools as a means of achieving some target design (striving, for example, to resemble a piece of of concept art), he prefers to approach 3d tools on their own terms and see where they lead him. O’Reilly then delivered the most killer line I’ve ever heard at a Q&A: Rather than using 3d animation merely as a means to an end, O’Reilly seeks “ends from the means”. In the process, he explained, his animation tends to become distinctive even when distinctiveness is not his primary goal.

Boy Geniuses

Later that day, ceMelusine and I got to watch Liz Ryerson speak at the annual Influences panel. Ryerson’s talk was my favourite of the conference, which should surprise precisely no one who’s ever met me. In it she provides an account of the high tech industry as a privileged class of individuals (aspiring “boy geniuses”, as Ryerson calls them) all seeking to be the first to discover and colonize some new interaction design gimmick so they might reap financial and social capital from their newly-claimed intellectual territory. (Consider, as one example, the swathe of indie game developers who attempted to create ‘the next Braid!’ in the wake of Blow’s initial success; they suffered, if I am understanding the talk correctly, from an acute case of “boy genius syndrome”.)

Ryerson went on to argue that those who strive to become ‘boy geniuses’ have, in their attempts to render the digital world safe and consumable for all, also left it beholden to the various commercial interests who incentivize and profit from our cultural tendency to praise ‘innovation’ above all things. Ryerson reminded us that there are other virtues worth pursuing; that digital forms can do more than ‘innovate’. Rather than (to reuse my previous analogy) questing for some shiny new game mechanic that will make one lucky soul several years’ salary on XBLA, Ryerson implored us to “embrace the new flesh”: To seek out difficult and even painful experiences that challenge and complicate the way we understand ourselves. To do otherwise, Ryerson warned, is to uncritically accept the exploitive ideology of silicon valley and the videogame industry.

Ryerson’s talk represents the culmination of a line of thought she’s been developing through her writing since I began following her a year ago. It’s the most convincing argument I’ve yet seen for the relevance of her game Problem Attic to our cultural canon (and I say this having myself spent a great deal of time arguing for Attic’s place in said canon). I believe Liz Ryerson is the most exciting thinker in videogames today. If you haven’t kept up with her work, I hope you will consider spending a bit of time on it. (Then, having done so, you can read her IndieCade talk here!)

At the end of the conference’s first day I spent the night in a sweltering motel room. ceMelusine was in the other bed and went out like a light; he promptly started snoring while some couple upstairs enjoyed multiple rounds of raucous sex. In that moment I would have preferred to be any of the three, but afterwards I appreciated having had what I judged to be an authentic LA experience.

Alternate Histories

The final two days of talks returned again and again to the subject of history, with many speakers aiming to preserve the experiences and contributions of marginalized people within the games industry.

anna anthropy chose to address the popular cultural narrative that indie games began with Braid in 2008, arguing that the true history of indie games stretches far into the past and features a diverse cast of individuals including yet not limited to the men depicted as ‘boy geniuses’ throughout Indie Game: The Movie. Members of what I might charitably call the conservative videogame movement tend to frame the presence of game people who are not cis/het Caucasian men as a recent phenomenon; the narrative claims they are attempting to ‘break into’ an industry that formed in their absence, and that for some reason this qualifies them for all manner of horrifying abuse. The truth, as anthropy explained in detail, is that these people were here from the beginning and it was in fact the forces of big industry who spent years trying to push them out.

Two other talks focused on the various institutional problems affecting game development and culture: One panel moderated by Shawn Allen dealt with race, while a town hall meeting the following day invited participants to discuss misogyny. One reason why it’s difficult to fit talks like these into a single hour is that we in the land of culture crit often feel pressure to adopt a ‘solutions-based’ approach to any problem we intend to call out (rooted, perhaps, in the conservative notion that to critique without fixing is merely to complain). Allen argued, however, that since institutionalized racism probably cannot be fixed in an hour we must speak even in the absence of clear-cut solutions.

In the wake of these talks, ceMelusine and I retreated to one of Culver City’s two Chipotle locations to eat tacos and talk. It occurred to us that the demand for an immediate and comprehensive solution to any difficult problem typically constitutes an effort to shut down conversation and thereby reinforce the status quo. The sense we got from Allen and the other speakers was that it’s important for conversation to move past this and, crucially, that we should be prepared to continue this conversation for a very long time.

On our third night at the motel (following our third day of LA sun) we discovered that the large metal apparatus underneath the windowsill was an air conditioner. (Did you know that ceMelusine and I are really dumb?)

Closing Ranks

On the final day of the conference Raph Koster and Greg Costikyan held a markedly grim conversation about the economics of present-day indie game development. They were suspicious of the increasingly-monopolistic games distribution business, which today is consolidated almost entirely under the auspices of Valve, Apple, Google and so on. At one point Costikyan expressed surprise that Valve had not yet cranked its royalty rate above 30%. Mind you, his surprise was not because he felt Valve deserved the extra revenue or that they could make any productive use of it; it was simply because no one in the games industry has the power to resist them anymore. It was vindicating on some level to hear Koster and Costikyan validate much of what I put down in Form and its Usurpers, but ultimately I’d say this made for poor consolation.

It struck me during this talk that modern internet services are dangerously opaque. Though we must partner with them in order to sell the things we make, we have no idea of their operating costs and, therefore, no basis on which to negotiate a fair deal. And although today’s tools permit us to work wonders, they also work against us: We are not their masters and we do not stand to profit. For those trying to make actual videogames for an actual living wage, there may be fewer opportunities in 2014 than ever in the history of our industry. As the medium matures, the walls of power rise.

Meanwhile, in what passes for the ivory tower of videogames, our educational process is maturing as well. Latoya Peterson, who sat on the aforementioned race panel, mentioned during Q&A that she is noticing a closing in the ranks of game education similar to the one she observed in news media. Whereas game studios usually favours a strong portfolio over any particular educational background, news organizations all but require a degree from prestigious institutions like Harvard or Yale; Peterson voiced her concern that our industry is becoming more like hers, with employers favouring a handful of specific schools and skillsets to the detriment of anyone who doesn’t make it into these institutions.

Back when I was university-bound I spent a lot of time bemoaning the fact that no Vancouver-based university could prepare me specifically for work in videogames. I resented that I might have to settle for a ‘general’ education in an industry people told me was very competitive; I never stopped to consider those who could not afford or access the same education as me, nor the negative impact of placing yet another gate before a culture that already has too many fucking gates in it. In retrospect, however, I’m glad I didn’t earn a degree in “videogames” and I regret that I might belong to the last generation of developers not to do so.

In the wake of IndieCade, during which the young ‘boy geniuses’ of DigiPen and USC each made strong appearances, I found Peterson’s comments worried me almost as much as Koster’s and Costikyan’s. I was glad to set foot upon Vancouver soil again, where our university programs are weird and unprepared and our games scene is broad and formless. Here there is an opportunity to build something new. Here the people I’d like to meet still have enough spare time to meet me; here there is room to become the sort of person I’d like to meet. I bag on Vancouver a lot, but having sampled a different scene for a few days I must concede that in some ways this city suits me: I still hate the rent, but I don’t much mind the climate.