One summer in 2008 we dreamt there was money in “indie games”.

It was a consensual hallucination experienced by thousands; a capricious belief, born from the resounding commercial success of games like Braid as juxtaposed against the dismal realities of AAA development work. Back then I counted myself amongst the dreamers.

I was born twenty years beforehand, in December ’88. As a shy middle class white boy growing up in Greater Vancouver, all I wanted to do was play with the computers my parents brought home. Yet where the previous generation, people like Richard Garriott and John Carmack, had spent their formative years hoping to become astronauts I spent them hoping to become Garriott or Carmack: A paragon of nerdness, an auteur of sorts, a so-called “game god”. This was the image I found in magazines and internalized; it was how I saw my future self whenever my daydreams pivoted towards optimism. (Sometimes I still catch it bubbling up from my id.)

Pictured: My subconscious, circa September ’99

By the time I entered high school, however, the magazine cover had changed: The picture grew darker as it became more concrete. Teams of less than ten had become greater than two hundred. Origin was now EA. DOOM was now DOOM 3. The axis of technology and capital had run amok, ‘maturing’ the videogame industry into an abject monstrosity; grown bloated and stiff, its body had begun to stink. I became increasingly aware that the future I sought, which I could not help but seek, was likely to consist of spending 12 hours per day modelling shin pads for EA Sports’ NHL franchise.

It is therefore easy to imagine what Braid represented to my 20 year old self, a student halfway through design school right in the middle of ‘The Great Recession’. It was a way out, or perhaps a way back. It was a dream. Here in the Summer of Arcade stood “indie games”, objects of both critical and commercial renown bounding forth from raw individual genius to seize the medium in their jaws. Here stood new game gods to paper over the old, illuminating an internet that increasingly offers nothing except magazine covers. On a conscious level I suspected this was all a mirage. But subconsciously it served as a pleasant fiction; a way to sleep soundly while adulthood carried my plans into the distance.

The city around me felt it too, as if some giant bell had sounded. The time was right for “indie”: The tools were there, the platforms were there and for a moment it looked like there was money. That summer the hype machine awakened, demanding to know what would be “the next Braid” and, implicitly: “Who would be the next Jonathan Blow?” More ambitious people than I “went indie” all over Vancouver, crowding the ranks of that incredulous few dozen who’d been doing this shit for years already. Speculation ensued.

Full Indie formed in 2010 as a meetup group for Vancouver-based “indies”. The timing could not have been better. 2010 represented the bottom of a long downward spiral for Vancouver’s game industry. Though it was once the biggest videogame city in Canada, places like Toronto and Montreal offered lower operating costs and had spent the past decade and a half luring its studios away. Vancouver was left only with EA Sports and a handful of stubborn holdouts. This vacuum left a collective of residual game makers tied to Vancouver for personal reasons but without meaningful work in AAA. The “indie boom” energized that collective, helping Full Indie accumulate hundreds of members very quickly.

The “indie dream” was well-suited to Vancouver. The city, after all, is a very dreamlike sort of place. At first glance it has everything for which a person could ask: Beaches, mountains, trees, a delightfully cavalier attitude about cannabis. It all makes for a gorgeous magazine cover. Yet like a dream, the city is insubstantial. Knock on a few of its luxurious façades and you’ll hear a hollow echo. Peek behind them and you’ll see nothing but cut corners; you’ll find the culture you thought surrounded you is but a rough facsimile of some other culture, transported here from some other place and time to serve the fantasies of whoever happens to be charging rent.

Vancouver is a creeping glass surface backed by money, wood and steel. Its tesselated forms fold ever outward from the SkyTrain lines, blanketing the Lower Mainland in their cool. It is a city that feeds on its own body even when there is nothing left to consume, levelling condos younger than I am to make room for newer, emptier and more overpriced condos. All landmarks are temporary; all history shall be erased. Every shred of culture is as a caterpillar in metamorphosis, an interstitial thing destined to emerge from its chrysalis one day as a proud unoccupied condo. The capital flowing through this place serves only to reconstitute the façade; it seldom comes to us.

Pictured: A gorgeous magazine cover

Sitting among the ~500 person crowd at the 2014 Full Indie Summit last weekend it’s obvious the dream of “indie” has long since faded, even if the label has managed to stick. Vancouver has given up on making “the next Braid” and striking it rich; the gold rush has ended, and now survival is the order of the day. I sit through half a dozen talks concerning themselves with how to balance marketing against actually developing a videogame (50-50), how best to interface with the games media news cycle (early and often) as well as the logistics of operating a full-fledged company that has only 2 employees (pork-flavoured ramen). Nobody’s daydreaming anymore; there are precious few “idea guys” in the room.

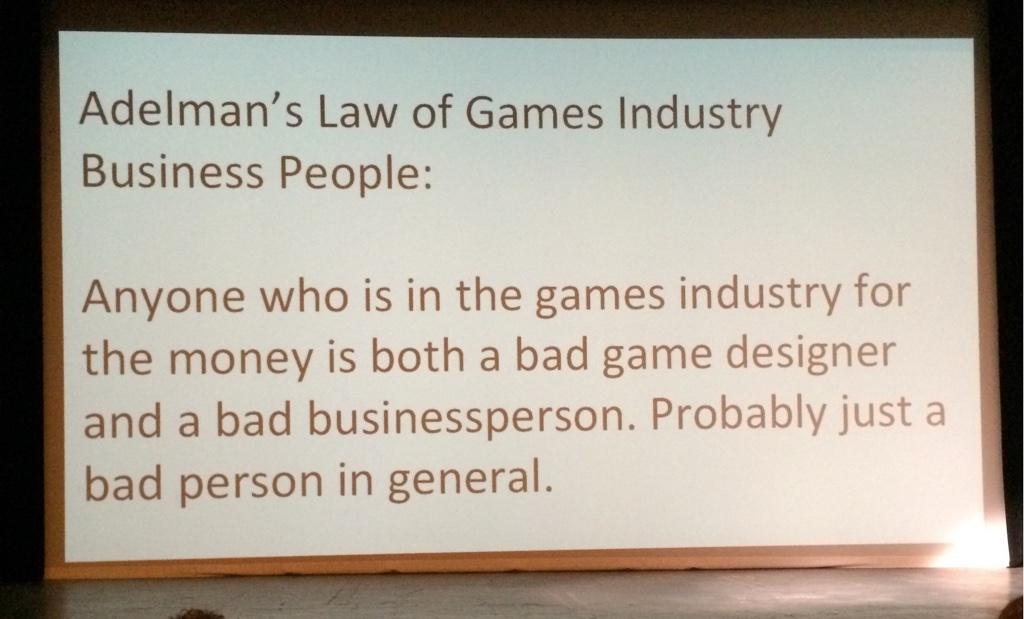

Today “Indie” is tired. It takes no pleasure in the empty posturing, the cheap cloning or the data-driven gold digging. It has no further use for speculators; it wants them to get out of the damn way. Dan Adelman, somehow formerly of Nintendo, drew the loudest applause of the show with this gem:

Pictured: Dan Adelman, circa quitting his job

Adelman claims the investors prospecting in “indie games” are wasting their time and our energy. On one hand they are unlikely to see large returns from their investments; on the other their efforts tend to oversaturate the market, making a living wage less attainable for we who make games as a vocation. It’s a losing deal for everyone involved. He goes on to claim that the price wars happening in venues like Steam and the App Store constitute a pointless race to the bottom. In the modern videogame market, Adelman suggests, we stand out not by charging less and less for our games but by charging more, positioning them as inimitable (and therefore expensive) rather than cheap and interchangeable with any old pile of junk.

Adelman slays the room by recommending that, rather than pursuing “indie games” in some vain attempt at profiteering, investors should consider opening a Subway restaurant instead: It pays $150,000/year, requires less than 10 hours of work per week to manage, and carries remarkably little risk. (Did you know Vancouver has more Subway locations than it has Starbucks coffee shops? They multiply like fruit flies here.)

Other speakers take a more existential tone. Alec Holowka, whose work on Aquaria helped precipitate the boom in 2008, begins his talk by asking the audience what the fuck “indie” even means. This piece represents my response to that question. To me “indie” was a myth in the classic sense of the word: An idea about individual people doing big things with videogames. But today that spirit is gone. Today we know that, like Vancouver itself, “indie” was a mirage; a magazine cover that has since been papered over, a condo knocked down to make room for other condos. Vancouver’s “indies” have become diaspora, a people brought together by the ghost of that ridiculous word in a city that threatens perpetually to swallow them. For the moment Full Indie remains, so here we sit in a refurbished theatre down Granville street where the creeping glass has yet to come for us. We’re all just trying to make rent.

Pingback: Notes on IndieCade | Brendan Vance

Pingback: The Ghosts of Bioshock | Brendan Vance