Glitchhikers is a game by ceMelusine, Lucas J.W. Johnson, Andrew Grant Wilson and Claris Cyarron that you can read about and play (for free!) on their website.

In Glitchhikers we follow our protagonist, the Driver, down some lost highway late at night. We may use the keyboard to change lanes, to accelerate or decelerate, and to look out the side windows. These mechanics provide no ‘utility’ in the sense we typically associate with videogames. They do not advance the player towards victory or defeat, nor do they compel her to spend money via microtransactions. They provide no gratifying feedback; there are no excruciatingly-rendered speed lines that spew onto the screen as the Driver accelerates to 120, nor does some down-pitched ‘whoosh’ effect from The Matrix fart out of the speakers every time she slows to 90. She is not competing against some artificial intelligence to snag the most victory tokens from the highway’s three lanes. There are no conspicuous resource crates scattered about for her to collect, no thousand-headed hydra of ‘mission objectives’ snapping at her from the corner of the screen. It is impossible to crash the car.

There is a school of thought in game criticism, which I have labelled The Cult of the Peacock, that doesn’t know what to do with Glitchhikers‘ game mechanics. It looks upon them with a screwed up face and, before making any other comment, utters something to the effect of “the driving controls don’t do anything!” It considers this to be a useful and valid criticism because it regards videogames as designed works whose purpose lies in some distant and mysterious dimension we call ‘fun’. It judges that since these mechanics do not immediately dispense ‘fun’ nor teach the player some skill with which to acquire ‘fun’ they must be superfluous, implicating their designers in the commission of some cardinal design sin. It insists these mechanics will make players confused and disoriented; that any cause not immediately followed by a gratifying and explicative effect is an act of heresy that must be purged from the product in service of clarity and craft. The customers have come to have ‘fun’, it believes, and so it seeks as its righteous purpose to deliver them unit after unit of fungible, systematized, thoroughly user-tested gratification. In other words, this school of thought believes that the purpose of a videogame is to perfect and perform ad infinitum the world’s most prolonged and least eventful blowjob.

Glitchhikers, for its part, is not particularly interested in exchanging gratification for money. It does not regard the player as a ‘John’ the way certain videogames do (either in the sense of “a prostitute’s client” or “a vessel for excrement”). Instead it regards her as one of many tiny inhabitants in its surreal virtual cosmos, imploring her to observe rather than affect; to interact rather than subjugate; to hold a memorable conversation with the world rather than merely ejaculate into it. The game does so, of course, through the very mechanics I’ve been describing, which far from being superfluous are essential to the form of the work.

The first such mechanic lets the Driver accelerate towards 120 km/h or decelerate towards 90. Sets of floating Brakelights glide along the highway far ahead of her, inviting her to speed up in hopes of catching them. When she attempts to do so, however, she finds the Brakelights always accelerate match her speed, coming just close enough to show us they aren’t actual cars yet too distant for us to touch. This makes the world both dreamlike and lonely, the Driver seeking out but never reaching her fellow highway inhabitants. We do not learn what the Brakelights are. Are they human, as she is? Or are they illusions? I imagine myself from their perspective, gliding away from some stranger pursuing them down the road. As I do so the world takes on a sudden Lynchian quality: The Brakelights must perceive us as extra-dimensional invaders barrelling after them at 120, perhaps reaching through the driver side window with fingers outstretched and eyes full of malevolent intentions. Why should they allow us to approach, not knowing what we are or where we come from? Glitchhikers is a dream about pursuit; yet as is the nature of dreams, a small shift in perception threatens to convert it into a nightmare.

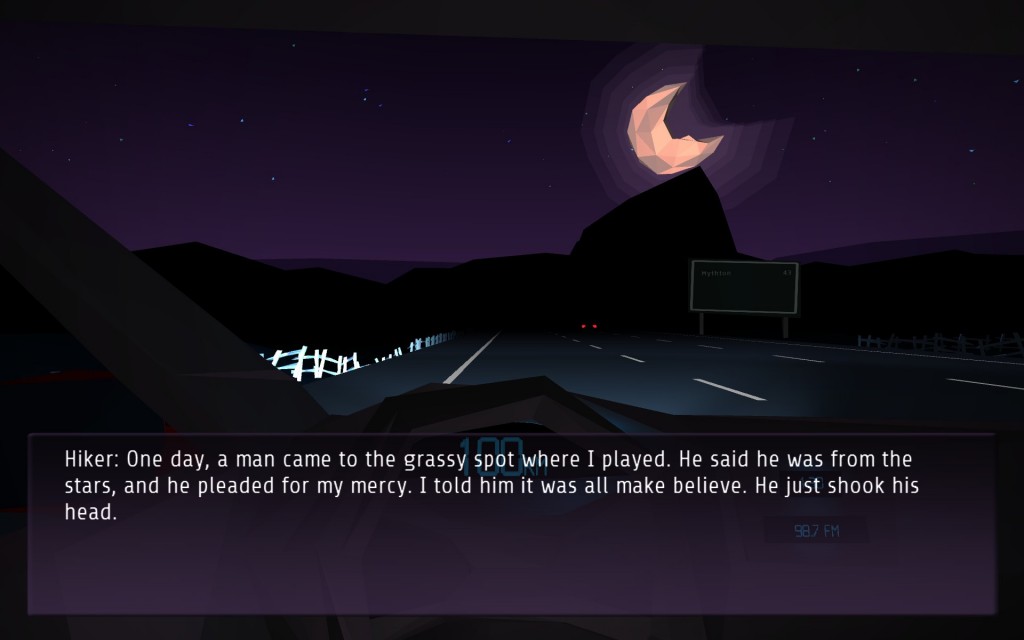

The game’s highway segments are procedurally generated, banking the player left and right at random. This brings the world’s enormous moon in and out of the player’s vision, sometimes sitting right in front of the windshield and other times lurking behind the rear window where we cannot see it. Occasionally it is only visible through the driver side window, allowing us to find it by using the ‘look left’ mechanic. The moon is a character unto itself, one that seems far more present than the Brakelights and thereby more comforting. Sometimes it’s made of space dust, pale and grey, but other times it’s made of copper; it likes to change its colour when the Driver goes through underpasses, perhaps just to see if she will notice. When located right front of us it fills the entire screen, keeping the Driver company for a few welcome moments. Then inexorably the road banks away and she finds herself alone again, facing nothing but black mountains and a giant starry void. The Hikers she encounters claim to live amongst these stars, but I’m not sure I believe them. Their stories interlock too tightly, like dream logic that makes sense only in the moments before the brain finishes waking up. These Hikers are too coy, appearing without invitation and vanishing before they’ve revealed any substantial truth. They glance fleetingly at the Driver, and by looking to the right we can meet their gaze. Yet in order to select something to say to them we must break eye contact and look back towards the road, almost as if the Driver were talking to the highway itself rather than her ostensible companion in the passenger seat. I don’t believe the Hikers are real. I read them as subconscious projections, the personified spirit of the highway and the late night drive. Like the road they serve to pass the time; yet like the road they cannot ease the Driver’s loneliness. Though the moon might be a fickle companion it is always there to drift back into view, and for that we cannot help but be grateful.

In the game’s final moments the ‘change lanes’ mechanic gains what the Cult of the Peacock might mislabel as a ludic purpose. The left lane leads to a cityscape glowing red against the world’s purple alpine wilderness. Situated as it is amidst mountains, pine trees and water it resembles the view of Vancouver one would see driving down from British Columbia’s interior. Yet rendered in a neon palette the image comes to represent something more: The sublime, mythical metropolis of science fiction, wherein it’s always night time and the streets always crawl with Brakelights. Perhaps this is the Driver’s destination, a place to stay if not genuinely a home. The right lane leads only into further darkness and presumably further driving. The Driver chooses, either consciously or through inaction, between two ideals: The city or the road, restlessness or loneliness, the destination for which we settle or the journey we can never complete. The choice, of course, is purely philosophical. There is no outro video portraying the devastating consequences of player agency; no uniquely-tinted nova to reassure the player of her potence; no damp, sticky rag we would prefer to forget. Glitchhikers is not about feeling powerful; it was not designed to stroke the player’s ego (nor, for that matter, to stroke any other part of the player). Rather, Glitchhikers allows us to participate in the Driver’s internal monologue while she struggles to construct the semblance of a meaningful life for herself, uncertain of where in the universe she would prefer to be.

Glitchhikers belongs to a tradition of game authorship, rather than game design. The idea is to stop designing videogames in service of ‘fun’ (or any other phenomenological sense), and instead to author videogames that explore ideas, themes, the human condition and so forth using literary techniques rather than behavioural conditioning and psychological experimentation. This tradition first came to my attention last year when I played Liz Ryerson’s Problem Attic, and has since consumed the vast majority of my thought, my writing and even my game programming. I believe it is our medium’s best response to the hollowness and utter banality of AAA-style formalism — I therefore like to describe it as ‘contentism’ — because it promises to connect us with the artistic traditions of film, novels, poetry, sculpture, painting and music (which is to say every other medium that ever existed) in ways the AAA videogame industry seldom manages to achieve.

There is all kinds of interesting work going on here, but its contributors suffer greatly from a dearth of funding (which results mostly from the false perception that multi-million dollar production values and extraordinary ease of use are the sole indicators of quality in interactive entertainment). Glitchhikers is free if you want it to be, but you can also choose to pay $10 for it. The question, if you ask me, is not whether you should purchase this videogame. The better question is: How many more Doom, Super Mario Bros and Tetris clones do you intend to endure before electing to put your money where your brain is?

“Keep driving, Driver. ‘Turtles All The Way Down’ is up next.”

It seems like you are singling out task completion as a culprit without going so far as to say it, and using that to draw a distinction between design and authorship. I think there is a part of what falls under “design” in this view that can create art out of mass-play which is impossible under the umbrella of “authorship”. It generally isn’t recognized as such because the default lens for critique of a game is one’s personal experience of the game itself, not the playing of the game en masse and the observation of how that takes place.

For example, if you detach from the investment in winning matchmaking games or chasing elite cosmetic items though still play, your actions are still participatory without “meaning” or achieving anything anymore, much like looking out a window or changing lanes. You become an observer, and if you want to, you can view your subject as art. Or to go one level of abstraction further, your active participation in a competitive/adversarial/”fun” environment contributes to a culture that can be viewed as a beautiful and usually temporary artifact of that game’s time and place in the universe.

In this view who is the author? The emergent properties in various scopes of a multiplayer AAA title don’t always deserve to be called art but I would say sometimes they very much do. In that case you have to give credit, I think, to everyone involved, which includes the players.

I’m not sure how useful it is to open the schema up to this abstraction, because your point is well taken regardless, but I wanted to comment that I think there is vast artistic value to be had borne out of the selfsame junky middle-seeking psycho-bait traits AAA game development so often turns towards. It’s just above and beyond the game itself, and often is tied to narratives or schools of thought that are only possible once the “content” is digested by the writhing masses far beyond what it originally was or represented.

I definitely take your point. I can get pretty extreme with my rhetoric about ‘design for mere gratification’ (particularly in this piece), but if we take the broader view there are indeed all sorts of ways we can interact with videogames that might elevate them as high as we care to go (and, of course, some credit must go to the designers who afforded these interactions in the first place).

I talk a lot more about my views on authorship vs. design in The Cult of the Peacock (although if I recall I was leaning more towards the word ‘art’ than ‘authorship’ back then). My essential claim is that the user-centric design principles we typically employ in videogames are about solving some specific problem (boredom, let’s say) through creating many testable iterations of our work, but that art is less about solving problems and more about delivering some authentically human form of communication (which is what I mean by ‘authorship’).

So as for whether I am zeroing in on “task completion” to make this distinction, I suppose I am not sure exactly what you mean. If we’re talking about, say, extrinsic motivation (achievements, fetch quests, EXP points, etc…) then I think we are largely in agreement here.

I think we are almost only in agreement! And I too wish for more meaning and not mindless entertainment. I wanted to explore the fuzzy space in between authorship and design which seems to be the crux of the medium known as “game”, but which is so hard to say anything concrete about.

Personally, it seems like so much of how we view games depends on our expectations of what a game is, where there is a heavy emphasis on agency and habitation of a game environment. But if you go to your local metropolitan museum of modern art you can surely find an interactive art installation that you’d never think to call a game but which may have more interactive depth than some indie art games which are largely just moving picture books (nothing wrong with that). Nevertheless you will immediately find a sense of play in the “consumption” of the art exhibit at the museum, and you might even devise an ad hoc game to play with it. Is this sense of play heightened precisely because it was not part of your initial expectations?

As a gamemaker you become a painter, a writer, a musician, an architect, as well as an engineer in various ways. How do the affordances you design relate to the products of your work wearing the other hats? And as a player, are you an observer or a dancer or a problem solver?

Most fundamentally I guess task completion is one term for a broad way of talking about gating that exists in the structure of a game which allows access to additional playspace (or simply content, like a cutscene) depending on user behavior. It is intrinsic to how you control the user experience, which is doubtless part of authorship but clearly design as well. And ultimately, because the medium is the message, the playspace a gamemaker provides is intrinsically part of any commentary on the human condition or self-expression they may be trying to communicate.

Although if I had to put my finger on the one thing that we’re both trying to talk about and give it a name, it’d be “artistic intention”. This is, of course, a nebulous idea but I think it has some weight and substance. And you can easily recognize when something lacks artistic intention.

I hope this was a usefully discursive response. XD

You’ve gotten me thinking a lot!

Pingback: ARCHIVE: Your Words Are Losing Structure: Brief Notes on The Falling Sun | Endless Campaign